Memoirs of the prisoners of the German camps. Memoirs of prisoners of concentration camps

Lyudmila's mother - Natasha - on the very first day of the occupation was taken by the Germans to Kretinga to an open-air concentration camp. A few days later, all the wives of officers with children, including her, were transferred to a stationary concentration camp, in the town of Dimitrava. It was a terrible place - daily executions and executions. Natalia was saved by the fact that she spoke a little Lithuanian, the Germans were more loyal to the Lithuanians.

When Natasha went into labor, the women persuaded the senior guard to allow them to bring and heat water for the woman in labor. Natalya grabbed a bundle with diapers from home, fortunately they didn’t take it away. On August 21, a little daughter, Lyudochka, was born. The next day, Natasha, along with all the women, was taken to work, and the newborn baby remained in the camp with other children. The little ones screamed from hunger all day, and the older children, crying with pity, nursed them as best they could.

Many years later, Maya Avershina, who was then about 10 years old, will tell how she nursed little Lyudochka Uyutova, crying with her. Soon the children born in the camp began to die of hunger. Then the women refused to go to work. They were herded with their children into a punishment cell bunker, where there was knee-deep water and rats swam. A day later, they were released and the nursing mothers were allowed to take turns staying in the barracks to feed their children, and each fed two children - her own and another child, otherwise it was impossible.

In the winter of 1941, when the field work ended, the Germans began to sell prisoners with children to farmers so as not to feed them for nothing. Lyudochka's mother was bought by a wealthy owner, but she ran away from him at night undressed, taking only diapers. She ran away to a familiar simple peasant from Prishmonchay, Ignas Kaunas. When she appeared late at night with a screaming bundle in her hands on the threshold of his poor house, Ignas, after listening, simply said: “Go to bed, daughter. We'll come up with something. Thank God that you speak Lithuanian.” Ignas himself had seven children at that time, at that moment they were fast asleep. In the morning, Ignas bought Natalya and her daughter for five marks and a piece of lard.

Two months later, the Germans again gathered all the sold prisoners in the camp, field work began.

By the winter of 1942, Ignas again bought Natalia and the baby. Lyudochka's condition was terrible, even Ignas could not stand it, he began to cry. The girl did not grow nails, had no hair, there were terrible abscesses on her head, and she could hardly hold on to her thin neck. Everything was from the fact that they took blood from the kids for the German pilots who were in the hospital in Palanga. The smaller the child, the more valuable the blood was. Sometimes all the blood was taken from small donors to the drop, and the child himself was thrown into the ditch along with the executed. And if it were not for the help of ordinary Lithuanians, Lyudochka would not have survived - Lucy, as Ignas Kaunas called her, with her mother. Secretly at night, the Lithuanians threw bundles of food to the prisoners, risking their own lives. Many children-prisoners through a secret hole left the camp at night to ask for food from the farmers and returned to the camp the same way, where their hungry brothers and sisters were waiting for them.

In the spring of 1943, Ignas, having learned that the prisoners were going to be taken to Germany, tried to save little Lyudochka-Lucita and her mother from theft, but failed. He was only able to pass on the road a small bundle with breadcrumbs and lard. They were transported in boxcars without windows. Because of the cramped conditions, women rode standing up, holding their children in their arms. Everyone was numb from hunger and fatigue, the children no longer screamed. When the train stopped, Natalya could not move, her arms and legs were convulsively numb. The guard climbed into the car and began to push the women out - they fell, not letting go of the children. When they began to unhook their hands, it turned out that many children died on the road. Everyone was lifted up and sent on open platforms to Lublin, to the large Majdanek concentration camp. And they miraculously survived. Every morning, every second, then every tenth was put out of action. Day and night the chimneys of the crematorium above Majdanek smoked.

And again - loading into wagons. We were sent to Krakow, to Bzezhinka. Here they were shaved again, doused with a caustic liquid, and after a shower with cold water, they were sent to a long wooden hut, fenced with barbed wire. They didn’t give food to children, but they took blood from these emaciated, almost skeletons. The children were on the verge of death.

In the autumn of 1943, the entire barracks were urgently taken to Germany, to a camp on the banks of the Oder, not far from Berlin. Again - hunger, executions. Even the smallest children did not dare to make noise, laugh, or ask for food. The kids tried to hide away from the eyes of the German warden, who, mockingly, ate cakes in front of them. The duty of the French or Belgian women was a holiday: they did not kick out the kids when the older children washed the barracks, they did not hand out cuffs and did not allow the older children to take away food from the younger ones, which was encouraged by the Germans. The camp commandant demanded cleanliness (for violating execution!), and this saved the prisoners from infectious diseases. The food was scarce, but clean, they only drank boiled water.

There was no crematorium in the camp, but there was a “revir”, from where they no longer returned. Parcels were sent to the French and Belgians, and almost everything edible from them at night was secretly thrown over the wire to the children, who were donors here too. Doctors from Revere also tested medicines on small prisoners that were embedded in chocolates. Little Ludochka survived because she almost always managed to hide the candy behind her cheek so that she could spit it out later. The baby knew what pain in the stomach was after such sweets. Many children died as a result of the experiments carried out on them. If a child fell ill, he was sent to the “revir”, from where he never returned. And the kids knew it. There was a case when Lyudochka's eye was injured, and the three-year-old girl was even afraid to cry, so that no one would find out and send her to the “revir”. Luckily, a Belgian was on duty, and she helped the baby. When the mother was driven home from work, the girl, lying on the bunk with a bloody bandage, put her finger to her blue lips: “Quiet, be quiet!” How many tears did Natalya shed at night, looking at her daughter!

Day after day went like this - mothers from dawn to dusk at hard work, children - under shouts and slaps on the back of the head, “walked” along the parade ground in any weather in wooden shoes and torn clothes. When it started to freeze completely, the warder "regretted", forcing her to stomp with her sick little legs on the slushy snow.

We walked silently to the barracks when we were allowed to go. Children did not know toys or games. The only entertainment was a game of "KAPO", where the older children commanded in German, and the little ones carried out these commands, receiving cuffs from them as well. The children's nervous system was completely shattered. They also had to attend public executions. Once, in the autumn of 1944, women found in a field, in a ditch, a young wounded Russian radio operator, almost a boy. In the crowd of prisoners, they managed to lead him to the camp, rendered all possible assistance. But someone betrayed the boy and the next morning they dragged him to the commandant's office. The next day, a platform was built on the parade ground, everyone was rounded up, even children. The bloodied boy was dragged out of the punishment cell and quartered in front of the prisoners. According to Lyudmila's mother, he did not scream, did not moan, he only managed to shout out: “Women! Brace yourself! Ours will be here soon! And that's it... Little Ludochka's hairs on her head stood on end. Here, even from fear, it was impossible to scream. And she was only three years old.

But there were also small pleasures. On New Year's Eve, the French, secretly of course, made a Christmas tree for children from the branches of some shrub, decorated with paper chains. The kids received a handful of pumpkin seeds as gifts.

In the spring, when mothers came from the field, they brought either nettles or sorrel in their bosoms and almost cried, watching how greedily and hastily, the children, hungry for the winter, eat this “delicacy”. There was another case. On a spring day, the camp was cleaned up. The children basked in the sun. Suddenly Lyudochka's attention was attracted by a bright flower - a dandelion, which grew between rows of barbed wire - in the "dead zone". The girl stretched her slender hand towards the flower through the wire. Everyone so gasped! An evil sentry walked along the fence. Here it is already very close ... The silence was deathly, the prisoners were afraid even to breathe. Unexpectedly, the sentry stopped, picked a flower, put it in his hand, and, laughing, went on. For a moment, the mother's consciousness even became dim from fear. And the daughter admired the sunny flower for a long time, which almost cost her her life.

April 1945 announced itself with the rumble of our Katyushas firing across the Oder at the enemy. The French transmitted through their channels that the Soviet troops would soon cross the Oder. When the Katyushas were in action, the guards hid in the shelter.

Freedom came from the side of the highway: a column of Soviet tanks was moving towards the camp. The gates were knocked down, the tankers got out of the combat vehicles. They were kissed, shedding tears of joy. The tankers, seeing the exhausted children, undertook to feed them. And if the military doctor had not arrived in time, trouble could have happened - the guys could have died from the abundant soldier's food. They were gradually soldered with broth and sweet tea. They left a nurse in the camp, and they themselves went further - to Berlin. For another two weeks, the prisoners were in the camp. Then everyone was transported to Berlin, and from there on their own, through Czechoslovakia and Poland - home.

The peasants gave carts from village to village, as the weakened children could not walk. And here is Brest! Women, crying with joy, kissed their native land. Then, after the "filtration", women with children were put into ambulances and rolled along their native side.

In mid-July 1945, Lyudochka and her mother got off at the Obsharonka station. It was necessary to get 25 kilometers to the native village of Berezovka. The boys helped out - they told their sister Natalia about the return of their relatives from a foreign land. The news quickly spread. My sister almost drove the horse as she hurried to the station. Towards them was a crowd of old villagers and children. Ludochka, seeing them, said to her mother in Lithuanian: “Either they took me to the revir or to the gas ... Let's say that we are Belgians. They don’t know us here, just don’t speak Russian.” And I didn’t understand why my aunt cried when her mother explained the word “to the gas” to that one.

Two villages came running to look at them, returning, one might say, from the other world. Natalya's mother, Lyudochka's grandmother, mourned her daughter for four years, believing that she would never see her alive again. And Lyudochka walked around and quietly asked her cousins: “Are you a Pole or a Russian?” And for the rest of her life she remembered a handful of ripe cherries, handed to her by the hand of a five-year-old cousin. For a long time she had to get used to a peaceful life. She quickly learned Russian, forgetting Lithuanian, German and others. Only for a very long time, for many years, she screamed in her sleep and trembled for a long time when she heard guttural German speech in the cinema or on the radio.

The joy of returning was overshadowed by a new misfortune, it was not in vain that Natalia's mother-in-law lamented sadly. Natalya's husband, Mikhail Uyutov, who was seriously wounded in the first minutes of the battle at the frontier post and later rescued during the liberation of Lithuania, received an official answer to an inquiry about the fate of his wife that she and her newborn daughter were shot in the summer of 1941. He married a second time and was expecting a child. The "organs" were not mistaken. Natalia was indeed considered to have been shot. When the police were looking for her - the political instructor's wife, the Lithuanian Igaas Kaunas managed to convince the Germans from the commandant's office that "she was shot that week along with her daughter." Thus, Natalya, the political instructor's wife, "disappeared". Great was the grief of Mikhail Uyutov when he learned about the return of his first family, in one night he turned gray from such a twist of fate. But Lyudochkin's mother did not cross the road to his second family. She began to lift her daughter to her feet alone. Her sisters helped her, and especially her mother-in-law. She took care of her sick granddaughter.

Years have passed. Lyudmila brilliantly graduated from school. But, when she applied for admission to the Faculty of Journalism at Moscow University, they were returned to her. The war “caught up” with her years later. The place of birth could not be changed - the doors of universities were closed for her. She hid from her mother that she was summoned to the "authorities" for a conversation and told to say that she could not study for health reasons.

Lyudmila went to work as a flower master at the Kuibyshev haberdashery factory, and then, in 1961, she went to work at the plant named after. Maslennikov.

IN THE GHETTO

On June 21, 1941, with two classmates, I went to the pioneer camp of the Minsk Radio Plant, which was located in the Raubichi area.

Telefunken's Elektrit radio plant appeared in Minsk in 1939 - before the transfer of the Polish city of Vilna to the Lithuanian state, the plant was dismantled and transported to Minsk. But they were able to mount and launch it only in the fall of 1940, when specialists were forcibly brought from Vilna. The radio receivers produced by this plant were world-class at that time ...

On the same day, June 21, my mother went to Essentuki for treatment, and my father went to Leningrad, on a business trip to the Svetlana plant. A three-year-old sister with a kindergarten went to the country.

On June 22, 1941, nothing disturbed our rhythm of life, but I was surprised that from the evening of June 22 and the morning of June 23, all male personnel disappeared from the camp. At night, my school friend Leonid was picked up by his mother in a ZIS-101 government car to take him to the Artek pioneer camp. Lenya was the son of the People's Commissar for Construction of the BSSR.

On the evening of the 23rd, when we were playing football, two planes flew over us: one with a star, and the second with unfamiliar black crosses. The flight was accompanied by machine-gun fire. The air battle, which we took for maneuvers, ended in the death of the red star aircraft.

On June 24, we saw a lot of planes with crosses on their wings, as well as strange human flows on the roads and the erratic movement of Soviet troops in different directions.

In the afternoon, we were gathered in the dining room, and the head of the camp announced the beginning of the war with Nazi Germany and that our victorious troops were already near Warsaw.

The guys of my age shouted "Hurrah", and the older girls, whose fathers served on the border, even shed tears.

By the evening of the 24th, tension had risen. There was a rumble and a rumble, and on the western horizon from the direction of Minsk, it seemed that the sun was not setting.

Early in the morning of June 25, refugees appeared: they were parents. They took their children and left in the direction of the Minsk-Moscow highway. From their messages, it became clear that the huge glow that we observed in the evening and at night was Minsk burning and destroyed by bombing. Refugees spoke of a large number of dead residents.

Soon my parents and two older brothers came for my second school friend Petya Golomb. This whole family worked at the radio factory, since they were taken out of Vilna as specialists. Petya knew Polish and Yiddish, and I knew Russian and English, which I started learning in the 6th grade. Since there was no one to come for me, I went with the Golombs towards Moscow.

On the way to the highway stretched a line of people-refugees. When we reached the tarmac road Minsk-Moscow, we were overtaken by German planes. Machine-gun bursts rang out. The crowd in horror rushed in different directions. There were many bodies left on the sides of the highway. These were the first things I saw in my life. dead people. There was a panic, crying and cries of the relatives of the dead were heard. Black smoke drifted along the horizon - from the burning of the tar pavement of the highway, on which fascist planes threw incendiary bombs. Burning military vehicles with equipment. The military units retreated in complete confusion, and we threw away the last things and quickened our pace, because we wanted to get to the city of Borisov (60 km from Minsk), but we could not stand the fatigue and fell exhausted at the edge of the forest by nightfall. We woke up from the clanging of caterpillars and from the German shouts of “Raus!”. The Germans were in black uniforms - tankers. As it turned out later, they were landing troops.

The men were immediately separated for a check - were they military personnel?

We were ordered to return to Minsk.

For two days we walked under continuous bombardment by aircraft and on the 27th we arrived in Minsk, but the Germans were not yet there. The city was all in ruins. Only charred chimneys remained from the wooden houses. Sadovaya Street, where I lived before the war, no longer existed, and where our house had been was a complete ashes. In it, I began to look for my collection of old coins. Found some coins fused with glass.

The question arose before me: “How to live?”. No friends, no relatives... Three-year-old sister Inna stayed somewhere in her kindergarten, which went to the dacha.

I went to look for at least someone, and on the outskirts of the city I found relatives of my mother's brother (a Russian family).

There were also victims of the fire: grandfather and grandmother - mother's parents. There was a roof over your head. With two boys (my relatives) we went in search of food. We were lucky. In a bombed-out confectionery factory, we dug up a cellar with flour and biscuits, and in a candy factory we found broken containers from where people scooped up the remains of molasses, which also came in handy. We snooped everywhere, and at the sorting railway station we found wagons with seeds, scored as much as we could carry.

On June 30, the Germans entered the city. Their troops moved day and night through Minsk towards Moscow. Tanks, motorized infantry: healthy, cheerful Germans armed with "Schmeisers" rode in trucks with songs. Artillery guns were dragged by huge horses, the likes of which we have never seen. It was a real eclipse, a parade of strength and arrogance.

On July 15, 1941, the first order of the German commandant's office appeared on the walls of the surviving houses and fences, from which it became clear that a ghetto was being organized in Minsk. We were advised to go to the Ostrashitsky town 25 km from Minsk in the hope that it would be calmer there.

Order

on the creation of a Jewish district in Minsk

1. Starting from the date of this order, a special district is allocated in the city of Minsk, in which only Jews must live.

2. All Jews, residents of Minsk, are obliged to move to the specified area within 5 days.

Jews found outside the Jewish region after this period will be arrested and shot.

3. Immediately after the resettlement, the Jewish region must be fenced off with a stone wall. The residents of this area should build this wall.

4. Climbing over the fence is prohibited. The German guards are ordered to shoot at violators of this paragraph.

5. An indemnity in the amount of 30,000 chervonets is assigned to the Judenrat.

6. Order in the Jewish region will be maintained by special Jewish detachments.

Field Commander.

This was the first order, then others followed: on the mandatory wearing of a yellow star, “armor” with a diameter of 10 cm on the chest and on the back - on all clothes on a white background with black numbers the number of the house where you live; about the ban on walking on sidewalks; about the ban on wearing any fur garments. Men are required to take off their hats in front of military personnel. There were many other prohibitions, for the violation of which - execution, execution ...

For two weeks we lived with friends in the Ostrashitsky town. Then a man who accidentally escaped from the nearby village of Logoisk came and said that all the Jews of Logaysk were buried alive in ravines (more than 500 Jews lived there at that time).

My relatives advised me to return to Minsk: “They won’t do such a thing in a big city…”.

I returned to Minsk. My relatives hid me in the basement, where I stayed for two weeks, and then it was decided to baptize me and put me in a Russian orphanage under the name Matusevich.

And so they did for a bribe to the clergyman. At that time, churches began to open everywhere.

Our orphanage was taken to Zhdanovichi, a suburb of Minsk. But at my naive request to the administration of the orphanage, I returned to the city to continue my studies in the 7th grade of the newly opened school. When I entered the classroom and looked around at the sitting children, everything inside me froze: my pre-war classmate Galya Misyuk was sitting at one of the desks! She knew me and my "conspiracy" could be instantly exposed! The teacher began with roll call. When my surname "Matusevich" was announced, I stood up in anticipation of the inevitable exposure.

During the break, Galya ran up to me and said: “Pavka, don’t worry, I understand everything!”

The study continued. The teacher made speeches about what happiness the German army brought to the Belarusian people, which would liberate the people from communists and Jews.

On November 5, 1941, we were taken to watch a documentary film about the victories of German weapons. Leaving the House of Officers after the cinema, we were horrified - people with posters on their chests were hung on the trees and lighting poles of all the alleys of the nearby central square: "We shot at German soldiers."

In the orphanage, I was unexpectedly called to the director's office. There were people I did not know and a policeman, as well as two children: a boy and a red-haired girl. An interrogation about my origin began. I answered as best I could. One of the questioners cut my hand with a knife and announced: “Here it is, Jewish blood.” The three of us were seized and taken to the ghetto. At the entrance, they kicked us into the wire and ordered the Jewish guard to take us to the Jewish orphanage. There was tremendous poverty, darkness, cold, hunger and stench. The children wandered slowly, like living skeletons.

They gave me a two-wheeled cart and told me to take the dead children to the cemetery. On November 6, returning from the cemetery, I saw Ukrainian and Lithuanian legionnaires from a distance, as well as Germans in SS uniform. They surrounded the entire area where the orphanage was located. I left the cart and ran to the area where the Deu-lei family, who were acquaintances of our family, lived.

The residents of the area were worried, and I could hardly get through. The fear that gripped all the inhabitants of the surrounded area is impossible to convey. They hid where they could. Only Grigory Deul himself was in the room, and he sent his wife and sons to another area of the ghetto.

On the morning of November 7, on a holiday, the assault literally began - shooting, screaming, crying. The Nazis with Lithuanian and Latvian detachments broke into houses, drove out everyone in a row, built in columns and took away, and partially took them away in an unknown direction. I miraculously survived this pogrom, because Grigory Deul had a German specialist certificate. He alone and I, as his son, were released. The rest (more than 100 people) were taken away from the yard.

In total, on November 7 and 8, about 29 thousand people were killed in one third of the ghetto. To perform the work necessary for the Nazis, only specialists were left: joiners, locksmiths, mechanics, turners. They were placed with able-bodied family members in other areas of the remaining ghetto.

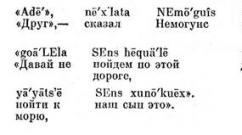

On November 10, about 30,000 people in unusual clothes were brought to the liberated areas in cars and placed in their homes. It soon became clear that these were forcibly deported Jews from Germany itself: from Hamburg, Berlin, Vienna, Bremen and Düsseldorf.

German Jews (for some reason they were called “Hamburg Jews”) found themselves in a more difficult situation than we are: they did not know either Yiddish or Russian, and they brought them to a foreign land with Mogendovids on their chests and on their backs.

At first, the German Jews did not communicate with us, because they were forbidden to do so. In addition, in the ghetto itself they were additionally fenced with barbed wire.

The famine forced these unfortunate people to offer their clothes and other things in exchange for some food.

Their fate soon turned out to be as tragic as that of all residents of the Minsk ghetto. Out of 30,000 German Jews, only one woman survived, who was helped to escape to a partisan detachment.

After all that had happened, I sought out the family of Petya Golomb, with whom I studied at school and with whom I left the pioneer camp. I told Petya's parents about my misadventures and asked to spend the night with them in a crowded apartment. To my surprise and joy, I was offered to live with them. We were given a place to sleep on a Russian stove in the kitchen. This was a salvation for me, in the literal and figurative sense, especially since the lonely tramp was fed by anyone with what they could.

I learned from the Golombs that the Germans were driving and bringing to the ghetto Jews living in the nearest suburbs of Minsk, as well as from the Ostrashitsky town.

I immediately began to look for a place where the residents of the Ostrashitsky town could stay, dreaming of finding my grandparents.

I was told that the newcomers were placed in the area of Nemiga Street. The inhabitants of this area just fell into the number of those killed, and the street went to the “Russian district”, as the other part of Minsk was called in the ghetto.

Risking my life and hoping for a miracle, I made my way to Nemiga Street, began to open apartments, and immediately felt the danger, because the empty apartments were teeming with marauders from the Russian region. When I opened the door of one of the apartments, I was horrified. There, side by side, lay a lot of old people in prayer capes, tales. All of them were covered in blood. Stabbed with bayonets.

Later it became clear that the Nazis showed special hatred towards believing Jews.

My search was in vain, and I had to come to terms with the thought of the death of my loved ones.

It is impossible to describe the situation in the ghetto after the first pogrom, when all the survivors felt the inevitability of their death.

One morning I went to the "Judenrat" for registration and immediately got into a street raid. We, who were caught, were pushed into cars and taken to the territory of the former GPU. There was a prison called "American". Next to this prison, we were building a second prison for German delinquent servicemen.

On walks, these arrested people were forced to jump like a frog on all fours around the prison until they were completely exhausted, and those who fell were poured with water and returned to the prison.

They fed us at this construction site once a day: a bowl of gruel plus 200 grams of bread in the evening, and they also gave us some small change in German occupation marks. My job was to prepare the concrete mortar and bring the bricks. For bricks, we went to a brick factory, where they pulled them straight out of the ovens, burning our hands.

On March 2, 1942, we were put into a covered truck to return to the ghetto. It was strictly forbidden to peek through the cracks from the car. When we were brought to the entrance of the ghetto, it was already dark on Republicanskaya Street. We heard noise, screams and swearing between our escorts and the Gestapo who stopped the car. The Gestapo men furiously demanded something, and our guards angrily objected to them.

We intuitively felt the danger.

Finally the gates opened and we entered the ghetto. Our guard Corporal Kau said: “Tell me thank you! Say a big thank you to me!" At first we did not understand what we should be thankful for, but when we drove into the streets, we saw hundreds of corpses lying around the houses.

It turned out that one of the largest pogroms in the Minsk ghetto took place without us. All those who were not working were taken to the Trostenets concentration camp for destruction, and those who resisted and hid were shot on the spot.

Some of the work columns that were returning, like us, were also wrapped up and sent to Trostenets, the death camp.

So our loud-mouthed corporal deserved his thanks ...

I immediately went to the Golombs, to 22 Stolpetsky Lane, not hoping to see them. However, fortunately, I was wrong. Their apartment was untouched. People hid in a shelter dug under a large Russian stove (these shelters were called "cache" or "raspberries"). 15 people from our apartment waited out the pogrom in this “raspberry”, equipped with a barrel of clean water and a bucket.

The Golombs, in turn, were surprised that I survived. Golomb's son Fedya (Faivish), a radio engineer, came home from work. They waited a long time for the second son David from the same working column of the radio plant, but they did not wait ... It was the hardest loss of a 25-year-old wonderful guy - the son of this family.

On July 20, 1942, our guard Kau unexpectedly forbade us to return to the ghetto, and we slept for three nights at the construction site. On the 4th day, having returned to the ghetto, they learned about another pogrom. The Germans undertook a search for the remaining, the so-called "cleansing". The territory of the ghetto by this time was reduced by two thirds.

After the pogrom on July 20, 1942, only about 30% of the original ghetto territory remained. Of the 130,000 inhabitants, no more than 30,000 survived, including German Jews, who realized that we are all equal in our destiny.

I recall a characteristic episode from our life. To look at the pogrom, the General Commissar of Belarus, General Kube, arrived with the Gestapo retinue and guards. Along with him was the commandant of the ghetto, Sturmbannführer Richter, with his cannibal shepherd dog. Kube inadvertently waved his hand sharply, and the dog rushed at the general, but the guard shot him. The next day, when returning to the ghetto by car, our construction team was stopped by commandant Richter, got into the cab, and we were taken to the Jewish cemetery along Sukhaya Street. Naturally, we decided that the end had come, but apart from the accompanying German and the commandant, there was no one at the cemetery. We were ordered to get out of the car and led to a fresh grave mound. It turned out that a dog was buried here. The senior master of our group was given a picture of a tombstone with a large cross. And we were ordered to collect a lab-radorite stone from rich tombstones and make a tombstone with the inscription “Hir ligt mein liber gunt” (here lies my beloved dog). For three days the whole group worked under the supervision of armed guards, making a tombstone with an inscription.

In the autumn of 1942, nightly pogroms began again in the ghetto. The reason allegedly was the exposure of underground groups and the search for partisans. Communication with the partisan movement did take place, but the Gestapo robbers surrounded houses with ordinary residents at night, drove half-dressed people out into the street and shot them without exception. Our house number 22 on Stolpetsky Lane also fell into the first night pogrom. Having broken the doors, the Germans rushed in with a cry - "Where is Tulsky?" (it was the head of the Jewish militia). At that time I was on the Russian stove, and suddenly Tulsky, who lived in the same apartment, climbed up to me. Immediately, both of us were thrown from the stove by the light of flashlights, and he was taken away. After 15-20 minutes, the Gestapo returned to the house, all the tenants were driven out into the street and ordered to stand facing the wall. Two or three Nazis stood behind us with machine guns, while others entered the house and looked for something, turning everything over. When they left, we were already saying goodbye to life, but all of a sudden they all left, and we were ordered to stand and not leave. After standing for more than an hour in this position and making sure that there was no one, we left and hid in the "raspberry". This was the only case when people survived in a similar situation - there were about 20 of us.

At the same time, we first became acquainted with the huge black trucks with diesel engines that drove into the ghetto every night. 40-50 people were driven into the bodies of trucks and, with a terrible crash of engines, they were taken away in an unknown direction. We soon learned that these were the so-called "gas chambers", in which, after 15-20 minutes, people died in terrible agony from exhaust gases.

At the end of August 1942, on one of the weekends on Sundays, I got into another raid. The SS men pushed me and 15 other people into a car and brought me to the territory of the former "garage of the Council of People's Commissars" on the Chervensky Trakt (Mogilevsky). Here they placed the production for the repair of guns and small arms "Giver-Wafenwerkstadt". When we got out of the car, they lined us up, counted five people at a time, and every fifth person was immediately hung on the nearest pole. It is difficult to convey our state at that moment ... Suddenly, a hauptmann (colonel) appeared in front of us - the head of the indicated production and announced in German:

"Whoever sabotages our instructions or violates discipline will suffer the same fate." We were placed in barracks with three-tier bunks along with prisoners of war. The barracks were surrounded by live barbed wire. It was essentially a mini concentration camp. We were forced to work 14 hours a day. My place on the bunk was in the third tier. Next to me on the second tier lay an elderly German Jew from Berlin, whose entire family was killed. One night he hanged himself from the rack of my bunks.

My duties included cleaning metal shavings from machine tools, then I cleaned the rust on rifle bayonets, on various parts of rifles and machine guns. In the future, I disassembled the rifles into parts. Weapons were brought from the fronts. I lost a lot of weight and constantly suffered from overwork and hunger. But when I was transferred to the "bronerai" (burning of weapons) section, where there was water, my immediate supervisor, non-commissioned officer Urlyaub (a resident of Koenigsberg), brought me to wash and clean the pots with food leftovers - this practically saved me from starvation.

After a month of work in a concentration camp, once a month, on Sundays, we were taken to the ghetto. In the future, such trips became regular, and sometimes they began to be taken to the ghetto after a week. On my next visit, I accidentally met Deul's son, Emmanuel. When he found out that I worked in weapons workshops, he asked: “Do I want to take revenge on the Nazis in a partisan detachment?” It was what I dreamed about during sleepless nights, not imagining that it could become a reality. He immediately set two conditions - to get 100 pieces of springs for a weapon cartridge ejector from the chamber and get himself a weapon, sawn-off shotgun or pistol. For 4-5 months, risking my life, I took out 100 springs in a jar of gruel, which we were fed. I was afraid of being exposed, because, firstly, I had to dismantle the gun locks, and secondly, when leaving the territory of the workshops, we were carefully searched by gendarme guards. Subsequently, I proceeded to the most dangerous part of the task - to take out the details of the rifle shotgun. In fits and starts at lunchtime, I adjusted and sawed off part of the trunk, then tucked it into a hole drilled in a piece of wood. I also hid other details, and then took them out. I managed to safely deliver these "poles" of firewood to the ghetto. For some time, the German guards did not pay attention to the smuggling of small sticks or wood logs from the territory of the workshops in the ghetto. Then it was banned, but by that time I managed to complete the task.

Firewood was badly needed, because it was terribly cold in the dwellings of the ghetto. Everything that could burn was burned in stoves and stoves. Existing furniture, interior doors were burned, even torches were chipped from the floors and walls for lighting. After the ban on taking out wood waste, some of our prisoners managed to bring pieces of wood to the place where we climbed into the car for a trip to the ghetto. At the moment of departure of the car, someone jumped off and threw the prepared firewood into the car, but soon this trick was noticed by the German accompanying us and beat the man half to death.

Once, while getting into a car for another trip to the ghetto (it was a February winter evening in 1943), I felt that one galosh from my foot was lost. When I looked over the back of the car, I saw a galoshes lying on the ground and jumped off after it. At that moment, I felt a terrible pain and lost consciousness. In the morning, when I woke up, lying on the floor in the kitchen, I was covered in blood, my whole body ached, my head and face were swollen, and the tenants of our apartment bent over me and lamented something. Then I was told that when I jumped from the car, the Germans (the driver and accompanying SS man) beat me unconscious with their feet and the butt of a Schmeiser and ordered the Jewish workers to throw me into the car. When the car arrived at the ghetto, at Yubileinaya Square near the Labor Exchange, the workers got off, and I was left lying unconscious in the car. They thought that I had been killed and they took me to the Jewish cemetery. There I was pulled out of the truck and ordered to be thrown into a mass grave. The car with the Germans left. I was thrown into one of the pits and then at the last moment they noticed that I was moving. The Golomb family and neighbors began to treat me as much as possible and even invited a doctor they knew. The next day, in the daytime, the tenants in the house were terrified of the appearance of the German and hid in the "raspberry", and I remained helpless on the floor. But it turned out that my overseer Urlaub had come, accompanied by a worker from the Gett, with whom I worked together in the workshops. A voice rang out: “Where is Paul?” When he saw me, he exclaimed: "Got get out" (My God). I told him that I jumped off the car for a fallen galoshina, and not for firewood. He left me a loaf of bread and a piece of sausage. He ordered the worker to leave, and in a whisper he said to me: “Paul, life in Wald” (run away into the forest). A week later, having recovered a little, I again came to the car in the morning and arrived at the concentration camp for work. My killers, seeing me, only grinned, expressing surprise.

In the spring of 1943, we were taken to work at 6 o'clock in the morning and back to the ghetto in the evening, in a column accompanied by a German escort. In May-June 1943 there were no more children in the ghetto. Once, when the work columns descended down the street. Republican to the gates of the ghetto, there was a delay. There was a stampede: another column was rising from above - workers of the Todt railway company. A child's cry was heard. And at the gate at the exit was one of the commandants of the ghetto - the Gestapo Ribbe. This beast in human form wedged itself into a crowd of workers and pulled a woman with a sack out of the column. Inside the bag was her 5-6-year-old son. Ribbe grabbed the sack, shook the boy out of it, and trampled the child on the tram tracks. Our column was 10-12 meters from this place, and we heard only the terrible cry of the mother. A few minutes later we passed by a torn baby. A direct witness to this heinous brutal murder was Rita Kazhdan, a prisoner of the Minsk ghetto, now living in St. Petersburg.

The end of spring and summer of 1943 was a very restless and disturbing time for the inhabitants of the ghetto. Constant night pogroms with raids by "gas chambers", looting by the Belarusian police, raids and murders. Every evening, gunfire was heard from different sides of the ghetto. All this demoralized the remaining residents, increased the feeling of hopelessness and depression. Constant hunger and hard labor killed faith in the successful outcome of these trials. But one day in August, Monya Deul waited for me and told me about the need to prepare for an escape from the ghetto, because they were waiting for the arrival of a guide. He checked the completion of my task, I gave him some of the springs. We agreed with him in detail on mutual communication. After another pogrom in the ghetto, I didn’t go to work, and I didn’t come home. M. Deul told the family where I lived that I had died. The head of the house passed on the authority that I had been killed - that was the routine. These were very difficult days - waiting for the guide. I spent the night in burning places, starving, and the risk of having a weapon was deadly. Finally, Monya came and announced the arrival of the guide "Katya" and the escape scheduled for the night. When they gathered at the appointed place, in one of the houses on the outskirts of the ghetto, at about one in the morning, a girl Katya, 13-14 years old, appeared. She got acquainted with us (there were 9-10 of us), checked the fulfillment of tasks according to the list, told about the route of movement and conditional gathering places in case of unforeseen circumstances. A little later, our people made passages with wire cutters in the wire fence, and we crawled behind Katya, observing all precautions (at the moments when the guards left our passage). Unexpectedly, unfamiliar people from the ghetto began adjoining us, eager to join the partisan detachments. An extremely dangerous situation was created, but we were forced to take everyone with us. When they moved away from the ghetto at a fairly distant distance, they lined up in a small detachment and so surprisingly safely passed through the streets of Minsk and went out of the city.

The most dangerous thing was the crossing of the Brest-Minsk railway line, which was heavily guarded. Approaching the railway, they heard the noise of an approaching train and lay down about seventy meters from the railway track. Suddenly there was a powerful explosion that lit up everything around. There was a rumble and rattle of falling wagons. The guards of the track began to launch flares, and the uninjured part of the guards of the train opened fire. Panic broke out in our team. The people who joined us, including women, jumped up and began to scatter, thereby unmasking us, and exposing themselves to German fire. The next day, the corpses of almost our entire group were transported to the Gettian cemetery. This story was not without punitive actions in the ghetto and executions of hostages. My age-mate Lenya Fridman and I ran into a nearby forest, which turned out to be a Lutheran cemetery, and hid until the end of the shooting. But since we lost the orientation of the route, the guide, and everything that we carried on assignment to the partisan detachment, we fell into despair and decided to return to the ghetto. After spending the night for two days in the ruins, on the third day in the morning, the two of us attached ourselves imperceptibly to a large work column and left the ghetto. Passing by the destroyed houses, we slipped into the burning place, tore off our identifying yellow armor, numbers and went in the direction of the resort village of Ratomki, that is, we took a landmark from the instructions of the deceased conductor. In the daytime, we managed to cross two railway tracks, then within three days we reached the Old Village, where the partisan zone began, through the forest. Seeing a large village from the edge of the forest, we did not yet know its name and spent the night in the forest. In the morning, hunger forced us to turn to the inhabitants of one of the outermost huts. When the hostess of the house saw two emaciated juvenile humanoid creatures, she invited us into the house without our request and gave us hot potatoes, pancakes with milk and a loaf of bread. It still seems to me that I did not eat such delicious food before the war. And to this day, I imagine the taste of that extraordinary food. The hostess also delighted us with the news that this village is our magical goal - the partisan region. In addition, she told us about numerous detachments of different names that come to this village, as well as about Minsk Jews who gather in the center of the village and form into various partisan brigades and detachments.

But considerable difficulties and disappointments lay ahead of us. The first enthusiastic and naive meeting was the day when we saw two young guys with red ribbons on their caps. “Uncles partisans,” we turned to them, and they called us “jews,” took away everything that we had and, at gunpoint, forced us to run back to the forest. We thought they were policemen in disguise. My partner Lenya completely lost heart and refused to enter the village again. In the afternoon I went alone, and Lenya promised to wait for me. In the middle of the village, I really saw a lot of men in Soviet military uniforms with ribbons and stars. I also saw a group of Jewish women and men who had made a successful escape from the Minsk ghetto, but from their mood I sensed anxiety and vagueness of perspective.

PARTISAN TERRITORY

In the village of Staroe Selo, among a group of partisans, quite unexpectedly, I saw three men in uniform with partisan ribbons. These were Ukrainian legionnaires with whom I worked in weapons workshops. They recognized me and after a friendly conversation they took me to the commander - the captain, who completed the group of new partisans. After listening to a story about my past and having received confirmation from the Ukrainian guys, the captain resolutely announced that he did not need youngsters without weapons. However, he announced that his detachment would leave for Nalibokskaya Pushcha after some time, and he agreed to temporarily join all the Jews in this village, and then send us to Stalin's brigade, which allegedly has a family detachment. I told this joyful news to a group of Jews whom I met in Staroye Selo, and ran to look for my partner Lenya, but I had to return alone - I did not find Lenya. A few days later, a group of partisans and we, a group of about twenty Jews, set off on a campaign. In three or four days we covered more than a hundred and thirty kilometers at night, and sometimes in the daytime - not without incidents - but this Pushcha was already a partisan zone. There, a group of Jews was ordered to separate from the fighting group of partisans and move towards the nearest village of Rudnya. When approaching the village, we saw the ashes and bare chimneys sticking out, but in the fields and gardens there were many women. It turned out that these were Jewish women from the family detachment No. 106 of the Brigade named after. I. Stalin, where the commander was Sholom Zorin. The commander of the entire brigade, General Chernyshev, was a bright personality. Detachment No. 106 was specially created for Jews who fled the Minsk and other ghettos, because not all partisan detachments accepted Jews during this period, arguing that women and children made it difficult for the detachments to maneuver, but many commanders did not hide their anti-Semitic attitude. The order to form a special family detachment came from General Chernyshev. In November 1943, there were 620 people in the detachment, among whom were people of different ages, including women and children. Women were engaged in harvesting potatoes and other vegetables in orphaned fields and gardens, as punitive fascist detachments burned the villages of the partisan zones along with the inhabitants. Naturally, after short conversations and inquiries, our entire group was enlisted in the detachment and distributed according to its intended purpose. Men - in combat groups, women - in household brigades. The partisan days have begun. It was necessary to equip life, build huts, prepare dugouts for the coming winter period, procure food, look for weapons and ammunition abandoned by the retreating Soviet troops in June 1941, repair the weapons found, and establish honey. points, stand on patrol, participate in the violation of German wires and communication cables, cut down power and communication poles, undermine bridges and "walk on a piece of iron", as well as take part in defense and various types of battles with the Nazis.

There I learned how to smelt tol from shells. It was dangerous but necessary work. We examined the found artillery shells, carefully unscrewed the fuses and immersed them in a container with water, lit a fire under it and smelted tol, which was poured into square shapes. I also had to participate in various economic activities.

But the main task of our detachment is to save the lives of former prisoners of the ghetto and concentration camps until they join the units of the Soviet Army. Under the victorious pressure of the Soviet Army, the 1st and 2nd Belorussian fronts, the retreating fascist groups entered the forests where partisan detachments were stationed, on July 10, at night, a German military unit broke into our base from the swamps, from which the brigade hospital was damaged with the wounded and doctors, as well as partisans from the economic unit. In that last fight many partisans died, and the detachment commander M. Zorin was wounded by an explosive bullet in the leg, which had to be amputated. But despite the difficult combat situation of that period, it was a long-awaited happy moment of anticipation of a meeting with our Soviet Army, which took place on July 13, 1944, and liberation from the Nazis. The partisans of our detachment were taken to Minsk in military vehicles. Soon we learned that the command of the 2nd Belorussian Front, together with the central headquarters of the partisan movement, ordered a parade to be held in the liberated Minsk Belarusian partisans which I was also a part of.

After the solemn march of columns of partisan brigades, I unexpectedly met a relative of Grigory Bashikhes, whom I considered dead, Grisha told me amazing news: from his own brother, who arrived from Moscow, as a representative of the People's Commissariat of Health, he learned that my parents were alive and living in the city of Zelenodolsk near Kazan. I was 16 years old. I without much difficulty issued a demobilization, received Required documents and "went" to his parents. In this case, the word “went” sounds inaccurate, because it took ten days to get to Moscow - 750 km. He rode on open platforms, on the roofs of wagons, rarely on locomotive tenders. All the way from Minsk to the station. Yartsevo war left its terrible mark. Not a single surviving residential building, uncleaned corpses along the road, refugees, cripples, the disabled and poverty. At st. Yartsevo, I climbed into the passenger car and on the third shelf drove to Moscow without waking up. When I got off at the Belorussky railway station in Moscow, it was as if I had entered a different world. I was struck by a well-dressed fussy crowd - women in colored dresses, many of them with painted lips ... I was also surprised at various patriotic posters and posters for theater and cinema. I had to get to relatives who lived near the Kursk railway station. When I went down to the subway, it seemed like a dream to me. My unexpected appearance amazed my relatives, because I had long been considered dead. They rushed to hug me, but I resolutely pulled away: they say, first of all, I need a bath, because I am all dirty and lousy. In the bathhouse, I put all my clothes in a "washer" and enjoyed the abundance of hot water, warmth and soap, which I used for the first time in three years. Returning to my relatives' house, I had to tell about the death of numerous close relatives of this family and about the fascist atrocities in the ghetto. It was surprising that Muscovites and residents of other regions of the mainland knew very little about the true state of affairs in the occupied territory of the USSR, and especially about the fate of the Jewish population. I also remember tea with sugar cubes for the first time in three years. And the culmination of my Moscow stay was an evening telephone conversation with my parents. When my mother heard my voice, she had a heart attack.

In September 1944 I came to Kazan to visit my parents. Approaching the railway station in Kazan, from the window of the car I saw my father waiting and with him a group of employees for joint factory work. After almost four years of unusual separation from my parents, the meeting was difficult to describe and did not go without valerian drops, especially after a brief story about the days spent in the ghetto and the death of relatives and friends.

Further, at the insistence of the parents, I had to take up textbooks - to remember the past and move on - studying at day and evening school. Then there was a technical school and the mechanical faculty of the Leningrad Forestry Academy.

But that's another story.

"I curse you, war..."

A small, fragile woman came to the editorial office and timidly asked: “Can I write to you about my childhood, about what happened to me, a little girl, during the Great Patriotic War?”

She came a few days later with a twenty-page manuscript, just as quiet and unassuming. Shrugging her shoulders, she suddenly began to doubt: “Is it necessary so much? Maybe I wrote too much, not about that. Or maybe it was worth not remembering this? After all, I’ve only collected crumbs from the experienced nightmare here ... "

Preparing the material for publication, we practically did not change the language and style of the author. No hand was raised. We can imagine how psychologically hard it was for Olga Ivanovna Klimchenkova to write these lines...

I was born in the Bryansk region, on the land that became a famous partisan region during the Great Patriotic War. Our small village - Podgorodnyaya Sloboda - is located in the Suzemsky district, on the southern outskirts of the vast Bryansk forests, in a picturesque area on the banks of the Sev River. Before the war, people lived here quietly, worked tirelessly and were confident in the future. The village stood out from all the others. According to the GOELRO plan, a power station was built on the river in 1926. The village had its own mill, butter churn, large collective farm garden and apiary. Under the Soviet regime, an elementary school and a nursery were opened, a club was built in which the library was located, circles worked, and films were shown for free twice a week. There was also a truck (one and a half), and its own threshing machine, and several mowers-mowers, a good herd of horses, a dairy farm, a pig farm, a poultry farm and a sheepfold, and a small brick factory. "Light bulbs of Ilyich" burned not only in houses, they illuminated the streets, sheds, warehouses. In the evening, when lights were lit on poles along the streets and all this was reflected in the river, there was such beauty that strangers, passing through the village for the first time, asked: “What kind of miracle is this, what kind of town is this?” They were answered: “This is not a town, this is a village, the Kommunion collective farm. People were surprised because in the whole district the electric light burned in houses only in the district centers - in Suzemka and Sevsk. There were sad times in the countryside before the war: the famine in 1933. But by 1941 everything was back to normal. Gathered good harvests. Although the lands there are podzolic and poor, the people worked with all their heart.

In autumn, the collective farmers received what they earned in kind. Carts loaded to the brim carried sacks of grain, apples from the collective farm orchard, jars of honey from the apiary. Each yard had its own chickens, geese, ducks, pigs, sheep, and a cow. The youth - the main instigator of all innovations in the life of the village - created their own brigades, organized competitions. Everything was done with fire. At the end of the field work, holidays were arranged. Tables were laid in the club, and if the weather was good, then right on the street. All products were allocated by the collective farm. They drank little, but the fun flowed like water. They loved to sing. They went to work, from work with songs. Thought, believed - it will always be so.

The war found me in a pioneer camp. It was quiet after lunch. Suddenly there was the sound of a horn and a drum roll. The children jumped up in bewilderment and rushed to the ruler. The banner and portraits of members of the Politburo were already being carried there. Understanding nothing, they froze in the ranks. The head of the camp, pioneer leaders and all the staff were at the site. "Guys! - raising his hand, said the head of the camp. - Tonight the Nazis attacked our country. They attacked like thieves - from around the corner, suddenly. Kyiv has already been bombed. The ruler rustled, but the order was not disturbed. The chief continued: “I have given you terrible news, but there should be no panic. You are Soviet pioneers, you are staunch Leninists, you are our fighting, reliable replacement. You must always be self-confident and believe in our country. The war will not last long. Victory will be ours!"

Two days later, my father came for me. A month later, at the end of July, we saw him off to the front. There was only one letter from him. In the same forty-first, he died in Ukraine near Kremenchug. Dad was on the tank, and the Nazis knocked out the tank. We were told about this by an eyewitness to his death. But after the war, for some reason, we received a notice that dad was missing. So at the age of eleven I became an orphan.

But the worst was yet to come. The old people, women and children who remained on the collective farm worked as before. Then there were even fewer people: several people were sent to drive away the collective farm herd to the rear, and girls and boys of non-military age constantly went to the front line for barrage work.

In August 1941, a stream of refugees stretched through the village, then military units went. Residents asked the commanders why they were retreating, but they reassured: "This is not a retreat, but a reorganization."

Collective farmers began to prepare to meet the enemy. Divided into all the horses - it turned out one for three families. Grain and everything of value was buried in the ground. Pigs were slaughtered and also buried in the ground. They hid everything that was possible from the enemy, and hoped that it would not be for long, ours would soon return.

The front was getting closer, but we didn't want to believe it. We believed in the invincibility of our glorious Red Army. But one night the whole village was awakened by a terrible roar. The windows in the houses rang, the walls trembled. People were running out into the street. Who fled to the cellar, who to the river, into the bushes. It became obvious that the war came close. That night there was a battle just three kilometers from Podgorodnya. And two days later we saw the Germans.

It was a terrible day. They immediately hanged a young man who, due to illness, was not drafted into the army. They hanged him because he stood up for his wife and child, who were driven out of the house by the soldiers. They blew up the power plant, burned the club and school libraries, arrested five girls. The girls wanted to leave the village on a boat, but they were noticed, they started shooting into the air, and they were forced to moor to the shore. The fugitive was locked up in an empty hut. Among them was my older sister. My mother and I were also kicked out into the street, but we were sheltered by neighbors (grandmother was sick there, and the Germans did not stay with them).

Fires burned in the streets all night. The soldiers carried everything from the pantries, sheds, shot at geese and ducks floating on the river, caught pigs and dragged them to the fires, roasted, feasted. barking German speech resounded over the village. Our village has not heard such a noise since the day it was founded.

The whole village knew about the arrest of the girls. And the whole night passed in fear: what will happen to them? In the morning the mothers went to the chief German with a request to let their daughters go. But the fascist was still sleeping, and they did not let him in. Only in the afternoon, when the Germans left, all the inhabitants rushed to that hut, knocked down the lock and released the unfortunate. After that, the Germans appeared several times in Podgorodny Sloboda, but did not linger - they hurried to Moscow.

The chairman of our collective farm, left for underground work, was in a partisan detachment, but often came home. The detachment was formed before the arrival of the enemy and was called "For the power of the Soviets." The base of the detachment was ten kilometers from our village, and the partisans were frequent guests with us. Residents helped them with clothes, food, fodder for horses. By mid-February 1942, the partisans liberated the entire territory of the Suzemsky region. In April 1942, the Nazis launched punitive sorties against partisans and self-defense groups in the Suzemsky region. In the villages they occupied, the Germans burned houses and killed civilians. In Suzemka and other neighboring settlements, people were herded into houses, sheds and set on fire. In our village, the Nazis burned everything that could burn: houses, sheds, buildings on the collective farm yard, warehouses, and even cut down the gardens. And the worst thing is that 25 people were shot. My mother and two older sisters and I managed to go into the forest to the partisans. The sisters were accepted by the fighters into the detachment, and my mother and I, along with other surviving families, lived in huts. By winter, dugouts were dug in a remote tract and called the village "Nowhere to go."

In March 1943, units of the Red Army liberated the city of Sevsk, our entire Suzemsky district. People rejoiced at the liberation, they planned the future: “We will go out to our ashes in April, while we live in the cellars, we will sow, build a school, houses, establish a collective farm.” But…

Parts of the Red Army retreated, surrendering the entire liberated territory to the enemy. The summer of 1943 was the most difficult for the partisans and their families.

Both day and night there were battles. Everything was burning and thundering around. And May, and June, and July, and August, the Bryansk Forest groaned. There were heavy losses on both sides. The forest was littered with corpses. We left the inhabited villages deep into the forests, but no one knew where our detachment was, who was alive, what to do, where and where else to hide in order to escape. Hungry, swollen, dirty, lice-ridden people climbed up to their necks into the swamp, into the nettle thickets.

There was no longer any livestock, no other food. They ate grass, linden leaves, acorns. Typhus, fever, dysentery came on. The command of the partisan formations decided to go for a breakthrough. During it, my mother, my sister, who was ill with typhus, and other families of the partisans, we were surrounded. In the swamp, where we hid for the night, we were taken prisoner. And then they were taken to the Lokot-Brasovo concentration camp, located on the territory of the Brasovsky district Bryansk region.

But first we were driven to the Nerus junction. They kept them there all day in a log house, which served as a latrine and garbage dump for the team guarding the junction. Hungry people rushed to the waste dump, where greened pieces of bread and potato peels were scattered. It rained all day. We sat on the wet ground. It was the end of July. In the evening we were all put into a dirty freight car and the doors were closed. People breathed a sigh of relief: although it was dirty and cramped in the carriage, it was dry and warm...

At midnight, the doors of the carriage opened with a clang, and two tall men, climbing into the carriage, began to illuminate the dozing people with lanterns. Near the door was a young woman, the choice fell on her. She was taken away. People moved, whispered, began to hide women. Mom laid her sister on the floor, put a bag of things on top of her.

Frosya (that was the name of the woman who was taken away) returned to the car in tears, and then they came for her again ... In the morning, the car was hooked up to the locomotive and dragged to the Kholmechi station. There we were dropped off and driven off. We walked 40 kilometers, surrounded by soldiers and sheepdogs. In the evening in the village of Lokot we were put in jail. On the floor of the cell lay dirty, brown-stained straw. There were also blood stains on the walls. The next day we were taken out into the courtyard, lined up in a column and driven to Brasovo, where there was a real concentration camp with two rows of barbed wire, under current, with towers, with sheep dogs, with torture chambers. We were kept there for about a month. They fed worse than pigs: they gave two old potatoes and a mug of water a day.

Two weeks before the liberation of our region and three weeks before the liberation of the entire Bryansk region, we were taken to Germany. The car was opened when food was brought - the same as in the camp: two potatoes and a mug of water. In the corner of the car there was a drain, where people at night, ashamed of each other, went in need.

In Germany, we ended up in a concentration camp in the city of Galla. It was September, and we were still given only potatoes and water. Every morning - construction on the parade ground, checks and punishment of the guilty in front of everyone. They drove to the field to collect stones. I was unable to lift the basket of stones, and my mother carried hers with one hand and helped me with the other. The straw mattress and pillow seemed downy after such work. The eyes closed instantly. On top of that, I, like other children, had blood taken several times during my stay in this camp. From hunger and hard work, my head constantly ached, my hands and legs trembled.

Every morning, the Nazis arranged entertainment for themselves - they gathered people on the parade ground, then dispersed women, children, and the elderly in different directions. Mothers did not let their children go, then they were beaten with whips. Having had fun, the Fritz let the children go to their mothers and again drove everyone into the barn. Except for the girls and young women, they were taken out of the camp, and no one knew if they would return. They returned, and the next day everything was repeated.

In early October, a group of fifteen to twenty people was selected from the new arrivals and taken to the city of Sanderhausen. This group included my sister and my mother.

In Sanderhausen, everyone was quickly dismantled into landowners' households. Only no one wanted to take our unfortunate family - a mother and two daughters. We were so emaciated, thin and pale that everyone turned away. Only in the evening a young woman, about thirty-five, appeared. She had nothing to choose from and she took us.

At the estate, we were immediately sent to the barnyard to clean the cowsheds and feed the cattle. The yard was very large: cowsheds, a stable, a sheepfold, pigsties, its own smithy, its own mill, two two-story houses. The first evening we cleaned until midnight. Then they received three potatoes in their uniforms and a quarter of a cucumber. With this they went to bed. I woke up a knock on the window and shouts: “Aufshtein! Shnel, shnel, Russian Schwein!” After cleaning the yard, we were each given a cup of chestnut acorn coffee with two thin slices of bread. After breakfast we went to the field.

We were wearing jackets and skirts, wooden shoes. In the field they drove out to work in late autumn and winter. I was constantly covered in boils. The hellish situation exhausted not only physically. The contemptuous attitude of the masters towards their slaves was unbearable. The hostess kept spitting as she passed us.

But I also had a defender here - the daughter of the hostess Anna-Lisa. When they punished me, saying, “We will take you to the police, from there you will be sent to a concentration camp,” Anna-Lisa always felt sorry for me, brought me a piece of bread.

It was 1944. Mom suffered the most in captivity. Slavery, hard work, constant hunger (she gave half of her meager rations to my sister and me), fear for the bitter fate of her daughters made my mother think of ending her life and me. She did not initiate her sister into her plans - she was already 21 years old, and she did not want to leave me for further torment. Mom stopped the opening of the second front. A captive officer who worked for another Bauer told us about this. The hope of liberation kept me from leaving this life. In April, American troops entered the city. The Nazis were less afraid of our allies. That day we were not sent to the field. We were picking potatoes in the basement. Anna-Lisa came running and said: “Mom told you to go out and go to your room. American soldiers have come to us, they want to see you all.” We heard the long-awaited: "From today you are free people." That day, for the first time ever, we ate potato soup. There were bread on the table, and even a few pieces of sausage. At parting, the Americans told us not to do anything else. But after they left, we again went to the barnyard.

In early May, all the prisoners were gathered in the Dora concentration camp. This death factory was located near the city of Naruhausen. There, in a cave, in Mount Kronstein, there was a factory where V-projectiles were produced. The concentration camp itself was located at the foot of the mountain.

The first liberated prisoners, brought by the Americans to this terrible place, found the still uncleaned corpses of hanged and unburnt convicts. I saw people still hanging on the gallows, two pits with ashes and unburned bones, a huge pile of hair.

It was a branch of the famous Buchenwald. The same barracks, the same towers with observers, the same electric barbed wire, the crematorium, the same shepherd dogs, the same human shepherd dogs. scary place, creepy place. The prisoners worked for 15-16 hours, they were not raised to the surface for weeks. They were considered classified and were doomed to death. When the productivity of the prisoner was already insufficient, his further path lay in the crematorium.

We were placed in barracks according to nationality. How many people were there! All Europe. We were well fed, we were allowed to walk freely around the camp, but we were not allowed outside the gates. Observers in American uniforms loomed on the towers. We stayed there May, June and half of July. Again we lived in complete ignorance of what would happen to us. Then representatives of the Soviet command came to negotiate with the Americans. "The motherland is waiting for you!" - with these words, the representative of the Soviet side ended his speech.

A few days later we were loaded into large trucks and taken in an unknown direction. There were conversations: "They will take them to France, and then on a ship - and to America, to process their plantations." Two or three hours later, the cars drove up to a small river. The first car stopped in front of the bridge, followed by the entire column. On the opposite bank there was a table covered with red cloth, there were people in Red Army uniforms, holding flags and speaking their native Russian. The brass band played marches. Seeing all this, the people in the cars stood up and began to cry.

It was not a soft cry, not even a loud sob. It was like the roar of a wounded animal - so the accumulated longing for the Motherland escaped ....

In September 1945 we returned to our native village. In the place where the house stood, weeds grew and the remnants of a dismantled Russian stove stuck out. We settled in the cellar, where we lived until the summer of 1949. After living in the forest, after hard labor, my articular rheumatism worsened and my heart ached. Mom suffered from headaches and heartaches. And my sister was losing her mind - abuse and beatings did their job. Towards the end of her short life, she finally lost her memory. They have long been gone in the world: no mother, no sister. Only I, a disabled person of the second group, is still alive.

I studied at school, and in the summer I worked on a collective farm, where at that time everything was done by hand. Those who lived in the post-war village, where the Germans "dominated", will understand how difficult it was. But I was in my native land!

Then I graduated from a pedagogical college and worked at a school. She married a military man, wandered around the Union a lot. She worked wherever possible - at a construction site, in the bookselling, in the military registration and enlistment office. She raised two wonderful sons. I have three granddaughters and one granddaughter. And my greatest desire is that there will never be a war, so that my grandchildren, even in a dream, would not dream of what I had a chance to experience.

Almost sixty years have passed since the end of the war, but it has not left the memory of those whom it covered with its black wing.

I curse you, war...

How many lives have you taken

Hurt how many people

Among them are innocent children.

People! Hear the call:

To keep everyone born alive

Block the road to war.

Happiness, let peace reign on earth ...

Prepared by Asya Mitronova.

Both of our heroines - Lilia Tikhonovna Khominets and Elena Nikolaevna Kolesnikova - were born in the Vitebsk region of Belarus. It was with the invasion of this republic that the Great Patriotic War began. Unfortunate Belarus was under occupation from the very first days of the war until July 1944. During the years of the Great Patriotic War, it lost every third of its inhabitants. Many of them died in concentration camps.

It was very painful for Lilia Tikhonovna and Elena Nikolaevna to once again mentally experience the horrors of captivity, for which we sincerely ask their forgiveness, but they found the courage to tell about something that should not be forgotten.

Liliya Tikhonovna Khominets

I was born in Vitebsk in 1937. Dad, Tikhon Nikolaevich Sokolov, worked at a brick factory, mom, Tatyana Leontievna, was a housewife, she sat with children. There were five of us: four girls, one boy, I am the youngest.

In the Finnish war, dad was drafted, he was wounded, he lay in the snow for a long time, got frostbite on his legs, and was treated in the hospital. And when the Great Patriotic War began, he immediately went to the front.

On July 11, 1941, the three-year occupation of Vitebsk began. The city was under the rule of the Nazis for almost three years - from July 11, 1941 to June 26, 1944. At first, my mother and I lived in a city apartment, and then we went to our grandparents in the village of Ostryane near Vitebsk. All the local men, not called to the front, but capable of holding weapons, went into the partisans. In autumn, roundups began in the village. The Nazis went from house to house and took everything they liked - from knick-knacks to livestock. Grandfather, who was trying to protect the yard dog, died from a stray bullet: while the German was chasing his grandfather who was blocking his way in a makeshift wheelchair, the dog jumped on his back and grabbed his neck. Fritz, in fright, pulled the trigger of his machine gun and began to shoot randomly. All this happened in front of my grandmother, she fell ill after her husband's death.

To tell the truth, during the years of occupation, there was more harm from the police than from the Germans. The locals who went over to the side of the Nazis, trying to curry favor, went to any meanness, betrayal, atrocities.

In December 1942, one such policeman, a neighbor who knew our family well, together with a German officer entered my grandmother's house, where we were all at that time. The eldest, 14-year-old Nina, read fairy tales to us, the younger ones. Grandmother and mother spun around the house. The neighbor pointed to Nina. The German looked at her and waved him off: "kinder" - the sister was small and thin. “What a child she is,” the policeman put his hands on his hips. “She’ll be fifteen soon,” and pulled Nina out of bed by the hand. She stumbled and fell in front of the front door. Later, my mother said that she noticed how the German moved a little to the side and winked at Nina, pointing to the door - they say, run. She jumped up, and in what she was - woolen socks on her bare feet and a sleeveless dress - jumped out into the yard.

The neighbor chased after her, knocked her down on the snow, hit her with a butt, and then grabbed her by the scythe and pulled her from the yard onto the road, along which the village guys, her peers, were already walking. Mom, who ran out after the policeman, only had time to grab grandmother's drying jacket from the rope and throw it after her daughter.

And we didn’t hear anything more about Nina until 1946, we thought she died in a concentration camp. But it turned out that she was not in the camp - she managed to escape along the way.