The mystery of the origin of iriston, digora and the great Tamerlane. Are Ossetians Muslims or Christians? Religious worldview of Ossetians Ossetians Digorians

Digorians

digorænttæ

Digorsky, Irafsky, Mozdoksky districts, Vladikavkaz, as well as the KBR, Türkiye

Russia, Russia

- North Ossetia North Ossetia

- Kabardino-Balkaria Kabardino-Balkaria

Türkiye Türkiye

Syria Syria

Digor dialect of the Ossetian language

Islam, Orthodoxy

Caucasians

Digorians(Ossetian digoræ, digorænttæ; singular - Digoron, iron. Dygur, Dyguættæ; singular - Dyguron) - a subethnic group of Ossetians, they speak the Digor dialect (within the framework of Lenin’s linguistic policy, until 1937 it developed as a separate literary language) of the Iranian group of the Indo-European language family. Speakers of the Iron dialect rarely speak Digor speech and, without communication experience, understand almost little of it. Digorians, on the contrary, for the most part understand Ironic speech and partially speak it, since Ironian is more widespread in Ossetia and in Soviet times was considered the only literary language of Ossetians, and therefore it was also taught to Digorians. According to the 2002 All-Russian Population Census of Russia, 607 people indicated themselves as Digorians, and according to the 2010 census, only 223 Digorians indicated their identity.

- 1 History of the Digorians

- 2 Digor dialect

- 2.1 Comparative features of the dialects and dialects of the Digor dialect

- 3 Culture

- 4 Famous Digorians

- 4.1 Laureates of the Stalin, State and Lenin Prizes

- 4.2 Heroes of Socialist Labor, Heroes of Labor of the Russian Federation, full holders of the Order of Labor Glory

- 5 Interesting facts

- 6 Links

- 7 Notes

History of the Digorians

In the “Armenian Geography” (VII century), among the tribal names there is the ethnonym Ashdigor - it is generally believed that this is a mention of the Digorians. On this and other (in particular, linguistic) grounds, it is assumed that the dialect division in the Proto-Ossetian language occurred quite early, in pre-Mongol times. The Digorians have preserved legends about the invasion of the Caucasus by Timur (Zadaleski Nana and Temur Alsakh) at the beginning of the 15th century.

Digorians make up the bulk of the population of Digoria - the western part of North Ossetia (Digorsky and Irafsky districts of the republic) and the Ossetians living in Kabardino-Balkaria (the villages of Ozrek, Urukh, St. Urukh, etc.). At the beginning of the 19th century, a number of Digor families from the foothill villages of Ket and Didinata moved to the territory of the modern Mozdok region. Here, on the right bank of the Terek, two large settlements of Digorians arose - Chernoyarskoye (Dzæræshte, 1805) and Novo-Ossetinskoye (Musgæu, 1809)

Unlike the rest of Ossetia, which joined the Russian Empire in 1774, Digoria became part of the Russian Empire in 1781.

In the first half of the 19th century, Digorians professed both Islam and Christianity. The Russian government, seeking to separate Christians and Muslims, resettles the Digorians to the plain and in 1852 the Free Mohammedan and Free Christian communities were formed. Mozdok Digorsk residents from the villages of Chernoyarsk and Novo-Ossetinsk were also Christians. A considerable number of Muslim Digorians moved to Turkey in the second half of the 19th century, where they settled compactly near the city of Kars (the villages of Sarykamysh and Hamamli)

Nowadays, most of the Digor residents of the Iraf region and those living in Kabardino-Balkaria profess Islam; predominantly Christians live in the Digor region. The influence of Ossetian traditional beliefs is significant both among nominal Muslims and nominal Christians.

Digor dialect

Compared to Iron, the Digor dialect retains more archaic features of the common ancestral language. In other words, in a number of phenomena of phonetics and morphology, the Digor and Iron dialects can be considered as two successive stages in the development of the same language."

The founder of Digor literature is the first Digor poet Blashka Gurzhibekov (1868-1905). In addition to Gurzhibekov, such writers as Georgy Maliev, Sozur Bagraev, Kazbek Kazbekov, Andrey Guluev, Taze Besaev, Yehya Khidirov, Taimuraz Tetsoev, Kazbek Tamaev, Zamadin Tseov and others wrote their works in Digor.

Writing in the Digor dialect existed (in parallel with writing in the Ironic version of the language) from the very appearance of Ossetian writing on a Russian graphic basis, that is, from the middle of the 19th century. However, gradually the proportion of writing in Ironian, which formed the basis of the Ossetian literary language, increased, which at times led to an almost complete cessation of the printing of Digor texts.

From the time of the establishment of Soviet power until 1937, Digor was considered a separate language, textbooks and other publications were published. However, in 1937, the Digor alphabet was declared “counter-revolutionary”, and the Digor language was again recognized as a dialect of the Ossetian language, and the progressive Digor intelligentsia was subjected to repression.

Today, there is a rich literary tradition in the Digor dialect, newspapers (“Digoræ”, “Digori habærttæ”, “Iræf”) and a literary magazine (“Iræf”) are published, a voluminous Digor-Russian dictionary has been published, as well as an explanatory dictionary of mathematical terms authored by Skodtaev K. B.. Collections of Digor writers are regularly published, various literary competitions and evenings are held. The Digorsky State Drama Theater operates. News programs are broadcast on radio and television in Digor. Some subjects are taught in the Digor dialect in primary grades in schools with a predominant Digor population. It is planned to open at SOGU named after. K. L. Khetagurova, Digorsky Department of Philology.

The Constitution of the Republic of North Ossetia-Asia essentially recognizes both dialects of the Ossetian language as the state languages of the republic; in Art. 15 says:

1. The state languages of the Republic of North Ossetia-Alania are Ossetian and Russian. 2. The Ossetian language (Ironian and Digor dialects) is the basis of the national identity of the Ossetian people. The preservation and development of the Ossetian language are the most important tasks of the government authorities of the Republic of North Ossetia-Alania.

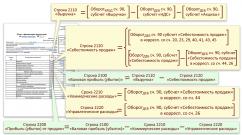

Comparative features of dialects and dialects of the Digor dialect

| Normal spelling of the Ironic version of the literary Ossetian language | Normal spelling of the most archaic Digor variant of the literary Ossetian language | Gornodigor dialect | Starodvalsky (Dvalian) dialect(until the 19th century) | Kudaro-Java (Novodval) dialect(continuation of Starodvalsky) | Alagir dialect(since the 20th century, replaced by Kurtato-Tagaur) | Urstual dialect And Chisan (Ksan) dialect | Kurtato-Tagaur dialect | Tual dialect(until the 20th century) | Translation |

| Salam | Salan | Salan | Salam | Salam | Shalam | Salam | Shalam | Salam | Hello |

| Kusynts | Kosuntsæ | Kosunčæ | Kusynch | Kusynch | Kushynts | Kusynts | Kushyns | Kusynts | (They work |

| Chyzdzhy tsæstytæ | Kizgi tsæstitæ | Kizgi honors | Kyzgy is chæstytæ | Chyzdzhi shæstytæ | Chyzdzhy tsæshtytæ | Chyzdzhy tsæstytæ | Chyzhdzhy sæshtytæ | Chyzdzhi is ashamed | Girl's eyes |

| Dzæbækh u | Dzæbækh uo | Jæbæh wo | Jæbæh u | Jæbæh u | Dzæbækh u | Dzæbækh u | Zæbækh u | Zæbækh u | Fine |

| Tsu | Tso | Cho | Chu | Chu/Shu | Tsu | Tsu | Su | Su | Go |

| Huitsau | Hutzau | Huchau | Huychau | Huyshau | Huitsau | Huitsau | Khuysau | Khuysau | God |

| Dzurynts | Dzoruntsæ | Jorunçæ | Djurynch | Zhurynch | Dzurynts | Dzurynts | Zuryns | Zurynts | (They say |

| Tsybyr | Tsubur | Kibir | Kybyr | Chybyr/Shybyr | Tsybyr | Tsybyr | Sybyr | Sybyr | Short |

Culture

- State North Ossetian Digorsky Drama Theater - in Vladikavkaz

- Song and dance ensemble "Kaft" - Digora,

- Statue of Jesus Christ opening his arms (Similar to the statue in Rio de Janeiro) at the entrance to the city of Digora,

- Newspaper "Digoræ",

- "Iraf" newspaper,

- Life of the "Iraf region"

- Museum in Zadalesk,

- Local Lore Museum of Digora,

- Monument to the Kermenists in the city of Digora,

Famous Digorians

Laureates of the Stalin, State and Lenin Prizes

- Akoev Inal Georgievich

- Gutsunaev Vadim Konstantinovich

- Dzardanov Andrey Borisovich

- Zoloev Kim Karpovich

- Zoloev Tatarkan Magometovich

- Medoev Georgy Tsaraevich

- Tavasiev Soslanbek Dafaevich

- Takoev Dzandar Afsimaikhovich

- Khabiev Mukharbek Dzabegovich

- Khutiev Alexander Petrovich

Heroes of Socialist Labor, Heroes of Labor of the Russian Federation, full holders of the Order of Labor Glory

- Bolloeva Poly

- Gergiev Valery Abisalovich

- Khadayev Akhurbek

- Tolasov Boris Konstantinovich

- The works of oral folk art of the Digorians “Temur Alsakh” and “Zadæleski Nana” talk about the campaign of Timur (Tamerlane) to the Caucasus at the end of the 14th century.

Links

- M. I. Isaev, Digor dialect of the Ossetian language

Notes

- Review of Ossetian subethnonyms and versions of their origin

- Abaev V. A., Ossetian language and folklore, vol. 1, M. - L., 1949. Cited. According to the editor: Isaev M.I., Digor dialect of the Ossetian language. Phonetics. Morphology, "Science", M., 1966

- Magazine "Revolution and Nationalities", 1937, No. 5, p. 81-82

- An electronic version of this dictionary is available for the ABBYY Lingvo shell

- Latest news releases on the Alania State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company website

- Full text of the constitution of the Republic of North Ossetia-Asia

| Ossetians | |

|---|---|

| Culture | Literature Music Cuisine Dancing Art Architecture Nart Epic Names |

| Ossetians by country | North Ossetia South Ossetia Ossetians in Georgia: Trialeti Ossetia, Trusovo Gorge Ossetians in Turkey |

| Attitude to religion | Christianity in Ossetia Islam |

| Ossetian language | Iron dialect (including Kudaro-Java dialect) Digor dialect |

| Subethnic groups | Ironians (Alagirians, Kudarians, Kurtatinians, Tagaurians, Trusovians, Tualians, Urstualians, Chsantsians) |

| Miscellaneous | History Ethnonyms Ethnogenesis |

Digortsi Information About

The Digorians make up the bulk of the population of Digoria - the western part of North Ossetia (Digorsky and Irafsky districts of the republic) and the Ossetians living in Kabardino-Balkaria (the villages of Ozrek, Urukh, St. Urukh, etc.). At the beginning of the 19th century, a number of Digor families from the foothill villages of Ket and Didinata moved to the territory of the modern Mozdok region. Here, on the right bank of the Terek, two large settlements of Digorians arose - Chernoyarskoye (Dzæræshte, 1805) and Novo-Ossetinskoye (Musgæu, 1809)

Unlike the rest of Ossetia, which joined the Russian Empire in 1774, Digoria became part of the Russian Empire in 1781.

In the first half of the 19th century, Digorians professed both Islam and Christianity. The Russian government, seeking to separate Christians and Muslims, resettles the Digorians to the plain and in 1852 the Free Mohammedan and Free Christian communities were formed. Mozdok Digorsk residents from the villages of Chernoyarsk and Novo-Ossetinsk were also Christians. A considerable number of Muslim Digorians moved to Turkey in the second half of the 19th century, where they settled compactly near the city of Kars (the villages of Sarykamysh and Hamamli)

Nowadays, most of the Digor residents of the Iraf region and those living in Kabardino-Balkaria profess Islam; predominantly Christians live in the Digor region. The influence of Ossetian traditional beliefs is significant both among nominal Muslims and nominal Christians.

Digor dialect

The founder of Digor literature is the first Digor poet Blashka Gurzhibekov (1868-1905). In addition to Gurzhibekov, such writers as Georgy Maliev, Sozur Bagraev, Kazbek Kazbekov, Andrey Guluev, Taze Besaev, Yehya Khidirov, Taimuraz Tetsoev, Kazbek Tamaev, Zamadin Tseov and others wrote their works in Digor.

Writing in the Digor dialect existed (in parallel with writing in the Ironic version of the language) from the very appearance of Ossetian writing on a Russian graphic basis, that is, from the middle of the 19th century. However, gradually the proportion of writing in Ironian, which formed the basis of the Ossetian literary language, increased, which at times led to an almost complete cessation of the printing of Digor texts.

From the time of the establishment of Soviet power until 1937, Digor was considered a separate language, textbooks and other publications were published. However, in 1937, the Digor alphabet was declared "counter-revolutionary", and the Digor language was again recognized as a dialect of the Ossetian language, and the progressive Digor intelligentsia was subjected to repression.

Today, there is a rich literary tradition in the Digor dialect, newspapers (“Digoræ”, “Digori habærttæ”, “Iræf”) and a literary magazine (“Iræf”) are published, a voluminous Digor-Russian dictionary has been published, as well as an explanatory dictionary of mathematical terms authored by Skodtaev K. B. Collections of Digor writers are regularly published, various literary competitions and evenings are held. The Digorsky State Drama Theater operates. News programs are broadcast on radio and television in Digorsk. Some subjects are taught in the Digor dialect in primary grades in schools with a predominant Digor population. It is planned to open at SOGU named after. K. L. Khetagurova, Digorsky Department of Philology.

The Constitution of the Republic of North Ossetia-Asia essentially recognizes both dialects of the Ossetian language as the state languages of the republic; in Art. 15 says:

1. The state languages of the Republic of North Ossetia-Alania are Ossetian and Russian. 2. The Ossetian language (Ironian and Digor dialects) is the basis of the national identity of the Ossetian people. The preservation and development of the Ossetian language are the most important tasks of government authorities of the Republic of North Ossetia-Alania .Culture

- State North Ossetian Digorsky Drama Theater - in Vladikavkaz,

- Drama folk theater of regional significance in the city of Digora,

- Song and dance ensemble "Kaft" - Digora,

- Statue of Jesus Christ opening his arms (Similar to the statue in Rio de Janeiro) at the entrance to the city of Digora,

- Newspaper "Digoræ",

- "Iraf" newspaper,

- Life of the "Iraf region"

- Museum in Zadalesk,

- Local Lore Museum of Digora,

- Monument to the Kermenists in the city of Digora,

- Monument to Vaso Maliev in the city of Vladikavaz.

Write a review about the article "Digorians"

Links

Notes

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Excerpt characterizing Digortsi

- What do you care? - the count shouted. Natasha went to the window and thought.“Daddy, Berg has come to see us,” she said, looking out the window.

Berg, the Rostovs' son-in-law, was already a colonel with Vladimir and Anna around his neck and occupied the same calm and pleasant place as assistant chief of staff, assistant to the first department of the chief of staff of the second corps.

On September 1, he returned from the army to Moscow.

He had nothing to do in Moscow; but he noticed that everyone from the army asked to go to Moscow and did something there. He also considered it necessary to take time off for household and family matters.

Berg, in his neat droshky on a pair of well-fed savrasenki, exactly the same as one prince had, drove up to his father-in-law’s house. He looked carefully into the yard at the carts and, entering the porch, took out a clean handkerchief and tied a knot.

From the hall, Berg ran into the living room with a floating, impatient step and hugged the count, kissed the hands of Natasha and Sonya and hurriedly asked about his mother’s health.

– How is your health now? Well, tell me,” said the count, “what about the troops?” Are they retreating or will there be another battle?

“One eternal god, dad,” said Berg, “can decide the fate of the fatherland.” The army is burning with the spirit of heroism, and now the leaders, so to speak, have gathered for a meeting. What will happen is unknown. But I’ll tell you in general, dad, such a heroic spirit, the truly ancient courage of the Russian troops, which they – it,” he corrected himself, “showed or showed in this battle on the 26th, there are no words worthy to describe them... I’ll tell you, dad (he hit himself on the chest in the same way as one general who was talking in front of him hit himself, although a little late, because he should have hit himself on the chest at the word “Russian army”) - I’ll tell you frankly that we, the leaders, “Not only should we not have urged the soldiers or anything like that, but we could forcefully hold back these, these... yes, courageous and ancient feats,” he said quickly. – General Barclay, before Tolly, sacrificed his life everywhere in front of the army, I’ll tell you. Our corps was placed on the slope of the mountain. You can imagine! - And then Berg told everything that he remembered from the various stories he had heard during this time. Natasha, without lowering her gaze, which confused Berg, as if looking for a solution to some question on his face, looked at him.

– Such heroism in general, as shown by Russian soldiers, cannot be imagined and deservedly praised! - Berg said, looking back at Natasha and as if wanting to appease her, smiling at her in response to her persistent gaze... - “Russia is not in Moscow, it is in the hearts of her sons!” Right, dad? - said Berg.

At this time, the countess came out of the sofa room, looking tired and dissatisfied. Berg hastily jumped up, kissed the countess's hand, inquired about her health and, expressing his sympathy by shaking his head, stopped next to her.

– Yes, mother, I will truly tell you, difficult and sad times for every Russian. But why worry so much? You still have time to leave...

“I don’t understand what people are doing,” said the countess, turning to her husband, “they just told me that nothing is ready yet.” After all, someone needs to give orders. You'll regret Mitenka. Will this never end?

The Count wanted to say something, but apparently refrained. He stood up from his chair and walked towards the door.

At this time, Berg, as if to blow his nose, took out a handkerchief and, looking at the bundle, thought, sadly and significantly shaking his head.

“And I have a big request to ask you, dad,” he said.

“Hm?..” said the count, stopping.

“I’m driving past Yusupov’s house now,” Berg said, laughing. “The manager, I know, ran out and asked if you would buy something.” I went in, you know, out of curiosity, and there was one wardrobe and a toilet. You know how Veruschka wanted this and how we argued about it. (Berg involuntarily switched to a tone of joy about his well-being when he began talking about the wardrobe and toilet.) And such a delight! comes forward with an English secret, you know? But Verochka wanted it for a long time. So I want to surprise her. I saw so many of these guys in your yard. Give me one, please, I’ll pay him well and...

The Count frowned and gagged.

- Ask the countess, but I don’t give orders.

“If it’s difficult, please don’t,” said Berg. – I would really like it for Verushka.

“Oh, go to hell, all of you, to hell, to hell, to hell!” shouted the old count. - My head is spinning. - And he left the room.

The Countess began to cry.

- Yes, yes, mummy, very difficult times! - said Berg.

Natasha went out with her father and, as if having difficulty understanding something, first followed him, and then ran downstairs.

Petya stood on the porch, arming the people who were traveling from Moscow. The abandoned carts still stood in the yard. Two of them were untied, and an officer, supported by an orderly, climbed onto one of them.

- Do you know why? - Petya asked Natasha (Natasha understood that Petya understood why his father and mother quarreled). She didn't answer.

“Because daddy wanted to give all the carts to the wounded,” said Petya. - Vasilich told me. In my opinion…

“In my opinion,” Natasha suddenly almost screamed, turning her embittered face to Petya, “in my opinion, this is such disgusting, such an abomination, such... I don’t know!” Are we some kind of Germans?.. - Her throat trembled with convulsive sobs, and she, afraid to weaken and release the charge of her anger in vain, turned and quickly rushed up the stairs. Berg sat next to the Countess and comforted her with kindred respect. The Count, pipe in hand, was walking around the room when Natasha, with a face disfigured by anger, burst into the room like a storm and quickly walked up to her mother.

- This is disgusting! This is an abomination! - she screamed. - It can’t be that you ordered.

Berg and the Countess looked at her in bewilderment and fear. The Count stopped at the window, listening.

- Mama, this is impossible; look what's in the yard! - she screamed. - They remain!..

- What happened to you? Who are they? What do you want?

- The wounded, that's who! This is impossible, mamma; this doesn’t look like anything... No, Mama, darling, this is not it, please forgive me, darling... Mama, what do we care about what we’re taking away, just look at what’s in the yard... Mama!.. This can’t be !..

The Count stood at the window and, without turning his face, listened to Natasha’s words. Suddenly he sniffled and brought his face closer to the window.

The Countess looked at her daughter, saw her face ashamed of her mother, saw her excitement, understood why her husband was now not looking back at her, and looked around her with a confused look.

- Oh, do as you want! Am I disturbing anyone? – she said, not yet suddenly giving up.

- Mama, my dear, forgive me!

But the countess pushed her daughter away and approached the count.

“Mon cher, you do the right thing... I don’t know that,” she said, lowering her eyes guiltily.

“Eggs... eggs teach a hen...” the count said through happy tears and hugged his wife, who was glad to hide her ashamed face on his chest.

- Daddy, mummy! Can I make arrangements? Is it possible?.. – Natasha asked. “We’ll still take everything we need…” Natasha said.

The Count nodded his head affirmatively to her, and Natasha, with the same quick run as she used to run to the burners, ran across the hall to the hallway and up the stairs to the courtyard.

People gathered around Natasha and until then could not believe the strange order that she conveyed, until the count himself, in the name of his wife, confirmed the order that all carts should be given to the wounded, and chests should be taken to storerooms. Having understood the order, people happily and busily set about the new task. Now not only did it not seem strange to the servants, but, on the contrary, it seemed that it could not be otherwise, just as a quarter of an hour before it not only did not seem strange to anyone that they were leaving the wounded and taking things, but it seemed that it couldn't be otherwise.

The question of who Ossetians are Muslims or Christians, and which religion is most widespread in North Ossetia, can only be resolved by considering the history of this people, starting from ancient times, when various tribes and ethnic groups lived on this territory.

History of the Ossetian people

Ossetians are one of the most ancient peoples of the Caucasus, having a specific religious culture and a rather complex structure of customs and beliefs. For centuries, their religion retained pagan roots, and then, under the influence of Christianity, the characters of pagan deities were firmly united with the Orthodox.

Therefore, answers to the questions of who the Ossetians were before the adoption of Christianity and what religious views they had must be sought in their historical roots, which originated from the Scythian-Sarmatians who founded the state of Alania here.

The inhabitants of the territory where North Ossetia is now located were tribes of Sarmatians and Alans, who back in the 9th-7th centuries. BC. settled here, creating a fairly developed “Koban” culture, the language of their communication was Iranian. Later, these settlements were raided by the Scythians and Sarmatians, who assimilated and formed new ethnic groups.

The appearance of the Sarmatian tribe of Alans happened in the 1st century. BC. and contributed to the emergence of the Alanian state in the 5th-6th centuries, the basis of whose government was military democracy. It included not only the current Ossetian territories, but also most of the North Caucasus.

The capital of Alanya - the ancient settlement of Tatartup - was located near the modern village. Elkhotovo. On the territory of the Alanian state, 2 ethnic groups emerged:

- proto-Digorians (Asdigor) - the western territories of Kuban, Pyatigorye and Balkaria, their population maintained economic and friendly relations with Byzantium;

- proto-Ironians (Irkhan) - eastern Alans (North Ossetia, Chechnya and Ingushetia), who were oriented towards Iran.

Christianization in the Alan Empire

In the VI-VII centuries. Byzantine preachers appeared in Alanya, introducing features of Orthodoxy into their life and religion. The process of Christianization was one of the forms of relations with Byzantium, which pursued its own political goals. With the help of Christian bishops and priests, the empire began to expand its sphere of influence and power in these lands, acting through local leaders through bribes and gifts, endowing them with various titles.

This happened in order to reduce the danger of an attack by nomadic tribes on the borders of Byzantium, which at that time inhabited the steppe and mountainous regions from the North Caucasus and Maeotis to the Caspian Sea. Therefore, the empire tried to provoke conflicts between them, and also tried to enter into an alliance with the steppe peoples in order to resist Iran.

The strategic position of the territories of the Alanian state contributed to the empire’s interest in its population, whom they, although they considered barbarians, sought to strengthen relations with them with the help of Christianity. Until the middle of the 7th century. independent Alania was an ally of Byzantium in confronting the Arab caliphate in the Caucasus.

After the end of the Arab-Khazar hostilities, the political influence of the Khazar Khaganate was greatly strengthened, which was Alania’s tactics in order not to fall under the rule of the Arab conquerors.

The fall of Byzantium, friendship with Georgia

At the end of the 10th century. The Alans enter into an alliance with the Rus, thus ensuring the victory of the Kyiv prince Svyatoslav over the Khazars, which helped the state free itself from the influence of the Kaganate and the Arabs. In independent Alanya in the X-XII centuries. a period of supreme political, military and cultural prosperity begins.

The Christianization of the Alans in these years was greatly influenced by friendly relations with the Georgian kingdom, where King David IV the Builder and Queen Tamara ruled. They pursued an active educational, missionary and peacekeeping policy throughout the region. An important moment in the history of the consolidation of Christianity as the religious worldview of the Ossetians was the emergence of the Alan metropolis. Georgian missionaries who came to the Ossetian lands were engaged in the construction of small Orthodox churches, which later began to turn into pagan sanctuaries.

In the Alanian state in the 2nd half of the 12th century. Feudal fragmentation begins, and then after the Tatar-Mongol raids it ceases to exist. In 1204, the crusaders' campaign and the capture of Constantinople led to the fall of Byzantium.

The era of rule of the Golden Horde led to the isolation of the Ossetian population, which survived only in the areas of mountain gorges, isolated from other peoples and states. During the period of the XII-XIII centuries. There was a decrease in the influence of Orthodoxy in the North Caucasus region; the bulk of the population adhered to semi-pagan beliefs, remaining isolated from civilization.

Religion of Ossetians - a mixture of Christianity and paganism

Forming mountain communities, Ossetians preserved their pagan religion for many years. Even during their subsequent migration to the plains, they adhered to these ancient views. According to the descriptions of travelers who visited them in past centuries and were interested in what religion the Ossetians professed, it was noted that they adhered to mixed religious rites.

Their religion intertwined Orthodox traditions, the veneration of Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary with semi-pagan holidays. Together with pagan deities (Ovsadi, Alardy, etc.), they worshiped Chiristi (I. Christ) and Madia-Mayram (Mother of God), etc. The Alans celebrated Orthodox holidays (Easter, the Descent of the Holy Spirit, etc.), strictly They kept fasts and went to the cemetery to remember the dead.

The Ossetian folk religion was created by a mixture of Christianity and paganism, partly Mohammedanism. Moreover, the adherence to religious rituals was not always accurate; much was confused and mixed up, which is associated with the missionary movements of not only Christians, but also Muslims.

Influence of the Russian Empire

Since the 18th century. the next stage begins: Christianity comes from Russia. Orthodox missionaries preached religious dogmas in the most remote mountain settlements, bringing with them goods for exchange and money to pay for baptism. Moreover, the highlanders managed to baptize not only themselves, but also their pets in order to get more coins.

Ossetian Christianity took a unique form: they believed in Jesus Christ, but also in their pagan deities. Ossetians did not go to churches built by Georgians, because the service there was conducted in Georgian. And only at the end of the 19th century. Local priests began to appear. After the founding of the Ardon Theological Seminary in 1880, where Ossetians studied, Orthodox churches also began to be built in settlements on the plains, which were supposed to resist the Muslim religion that had spread during these years.

Ossetians (Muslims or Christians) lived in small groups in the mountain gorges, continued to celebrate their traditional holidays and pray to their pagan deities.

Islam in Ossetia

Information about the preaching and acceptance of Islam by some families indicates its spread in the territory of Alanya back in the 7th-10th centuries, after the Arab campaigns. According to some sources, minarets were functioning already during the time of the Golden Horde, one of which, Tatartup Minarets, was destroyed in the 1980s.

However, in the official history of Ossetians it is generally accepted that wealthy feudal lords (Digorians, Tagaurians, Kurtatinians) began to accept Islam from the Kabardian princes only in the 16th-17th centuries. Moreover, the poor mountaineers at that time remained Christians, but gradually also adopted Islamic ideas. By the beginning of the 19th century. Most of the families were Muslims, with the exception of the Alagir and Tual communities.

During the Caucasian War (1817-1864), the propaganda of the Muslim religion began to prevail and came from Dagestan: the arrival of envoys from Imam Shamil helped spread Islamic ideas to 4 more mountain communities.

In the second half of the 19th century. The Russian government, following an anti-Islamic policy, forces Muslims to settle separately from Christians to prevent the further strengthening of the influence of this religion. Islamic villages had their own imams, who received education in Dagestan and Kabarda, the spread of Arabic writing began, and religious publications were published. The Caucasian War, which lasted almost 50 years, caused a partial resettlement of highlanders and Ossetians to Turkey.

Active anti-Muslim policies during the Russian Empire continued after the 1917 revolution by the communist government, along with the propaganda of atheism. During Soviet times, Islam was persecuted and banned.

Since the late 80s of the 20th century, there has been an increase in the influence of the Muslim religion, which is expressed in the adoption of Islam by Ossetians, who came from Muslim families.

Deities of folk religion

The native Ossetian religion believes in the existence of a God who rules the world (God of Gods). Below him there are other deities:

- Uacilla - the god of thunder and light (Gromovnik), the name comes from the biblical prophet Elijah;

- Uastirdzhi or Saint George is the most important deity, the patron of men and travelers, the enemy of all murderers and thieves;

- Tutir is the ruler of wolves, people believe that by respecting him, they divert wolves from attacks on livestock and people;

- Falvara is the most peaceful and kind deity, protector of livestock;

- Afsati - controls wild animals and patronizes hunters, looks like a white-bearded old man sitting on a high mountain, it is for him that the traditional 3 pies are baked, calling for good luck in life;

- Barastyr is the deity of the afterlife who cares for the dead in both heaven and hell.

- Don Battir is a water ruler who owns fish and patronizes fishermen.

- Rynibardug is a deity who sends diseases and heals them.

- Alard is an evil spirit that sends mass diseases - a monster with a scary face.

- Khuitsauy Dzuar - patronizes family and old people.

- Madii-Mayram - protects and patronizes women, the image is taken from Saint Mary in Christianity.

- Sau Dzuar is the “black” patron of the forest, protecting against fire and deforestation, etc.

Religious holidays in Ossetia

Numerous holidays in Ossetia differ in form and content, and in mountain villages they differ in their rules and customs. The main religious festivals of Ossetians are as follows:

- Nog Az (New Year) is celebrated on January 1 by the whole family, when treats are put on the table: traditional 3 pies, fizonag, fruits and festive dishes. A Christmas tree with toys is set up for children. The eldest, sitting at the head of the table, reads a prayer to God for the blessings expected in the coming year.

- Donyskafan - celebrated after 6 days, in the morning all women take jugs of “basylta” and go for water, where they pray for prosperity and happiness in the family, carry water home and spray all the walls and corners, wash themselves with it. It is believed that such water helps purify the soul; it is stored for future use.

- Hayradzhyty Akhsav - celebrated at night to appease the devils who, according to ancient legends, once lived with people. On “Night of the Devils,” it is customary to cut a kid (chicken, etc.) and bury its blood so that no one will find it. The table set at midnight with refreshments was first left for the “unclean”, and then the whole family feasted.

- Kuazan (corresponding to Easter) - marks the end of Lent on the first Sunday after the full moon in April. All preparations are identical to the Orthodox holiday: eggs are painted, pies and meat are prepared. At the festive table, the eldest in the family prays, turning to Jesus Christ about everything that Ossetians believe in: about the good for the family, about the remembrance of deceased relatives, etc. A holiday for the whole village (kuvd) is held, general fun, dancing, and visiting neighbors .

- Tarangeloz is one of the oldest traditional celebrations, celebrated 3 weeks after Easter. Tarangeloz is the name of the fertility deity, whose sanctuary is located in the Trusovsky Gorge. A sacrificial lamb is brought to him, the holiday is celebrated for several days, and races are organized for young people.

- Nikkola - the name of an ancient saint, known since the time of Alanya, is considered the deity of cereals, who helps to harvest the crops. The holiday falls in the second half of May.

- Rekom is a men's holiday, named after the sanctuary, especially revered among the mountaineers of the Alagir Gorge. According to tradition, a sacrificial lamb is slaughtered, national festivities and sports competitions are organized. During the festival (7 days), many families move into temporary buildings located near Rekom, ritual dances and processions are organized around the sanctuary, and neighbors from other villages are invited to tables with refreshments.

- Uacilla is the Thunder God, who takes care of everything that grows from the earth, a traditional holiday of agriculture since the time of Alanya. Its sanctuaries are located in different places, the main one in Dargavs on Mount Tbau. For the festive table, pies are baked, a sheep is slaughtered, and prayers are offered during the feast. Only the priest can enter the sanctuary, who brings offerings and a bowl of beer brewed specially for this day.

- Khetaji Bon is the day of Uastirdzhi, which helped the Kabardian prince Khetag escape from the enemies who were persecuting him for accepting Christianity. Celebrated in the Holy Grove near the village. Suadag on the 2nd Sunday of July is a national holiday with the ritual of sacrificing a ram and a feast.

Religions in Ossetia: XXI century

The question of whether Ossetians are Muslims or Christians can be answered accurately by looking at statistics that confirm that 75% of Ossetians are Orthodox Christians. The rest of the population professes Islam and other religions. However, ancient pagan customs are still practiced and have become firmly established in the everyday and family relationships of representatives of the people.

In total, 16 religious denominations are now represented in Ossetia, among which there are also Pentecostals, Protestants, Jews, etc. In recent years, attempts have been made to create a “neopagan” religion, an alternative to traditional beliefs, but based on tribal rites and the way of life of the population.

Center of Christianity in the North Caucasus

North Ossetia is the only Christian republic in the North Caucasus; Vladikavkaz is home to the dioceses of the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC), which unite the believers of this region.

The native religion of the Ossetians has its own national identity and can become the basis for the existence of Orthodoxy in this country, which preserves Christian values and the heritage of the Alans. The Russian Orthodox Church in Vladikavkaz begins work on the development of Ossetian-language worship, beginning the translation of Christian texts into the Ossetian language. Perhaps the tradition of holding Orthodox services in their native language will return to the ancient churches scattered in mountain settlements.

The policy of the government of North Ossetia within the Russian Federation is aimed at preaching and strengthening the Orthodox faith among Ossetians (Muslims or Christians).

Recently, the “Alan issue” has become more acute online. In this regard, let us refresh our memory of Bersnak Dzhabrailovich’s research on the origin of the historical Iriston and his connection with the legendary commander Tamerlane, as well as the role of Digora in the ethnogenesis of modern Ossetians

The Alagir Gorge, according to many researchers, is considered the center of the formation of the Ossetian (Iron) people. The process of this formation ended with Timur's campaign in the Central Caucasus at the end XIV century, when an Iranian-speaking tribe invaded the Alagir Gorge through the “ArgIi Naar” and exterminated the local inhabitants living there - the Alans. There is a point of view that the Iranians appeared here much earlier - during the Mongol campaigns of the 13th century. “In any case,” says B. A. Kaloev, — after the Mongol invasion there were much more Ironians than Digorians.”(1)

Without rejecting this point of view and the statement of V.Kh. Tmenov, that “here in the mountains it happens in the XIII-XIV centuries. the final formation of the ethnic type and the main features of the culture and life of the Ossetians” (2), we are still inclined to believe that it was Timur’s campaign in 1395 that led to the formation of the Ossetian people. This is evidenced...

and genealogical legends of Ossetians. Thus, according to B.A. Kaloev, “the appearance of many clans in Central and South Ossetia dates back no earlier than the 15th-16th centuries.”(3)

In Ossetian folklore, in the Digor versions, there are legends about the struggle of the people against the hordes of Timur, the Irons do not have such legends, although everyone knows that Timur was on the territory of Ossetia and brought terrible destruction, which should not have remained out of sight and not recorded in the memory of the people , who lived here, like, for example, among the Digorians.

The absence of legends among the Irons about opposition to Timur may mean: firstly, that they were loyal to Timur, if at that time they already lived in the Alagir Gorge; second, they were in Timur’s convoy. From both cases it follows that they did not participate in the fight against Timur, especially since in the Digor legends there is even a motif of kinship with Timur, who married three sisters in Ossetia. According to one of the legends, “Timur’s older sister gave birth to a son, Digor, from whom the Ossetians-Digorians descended; from his middle sister, a son Irau was born – from him the Ossetians-Ironians descended; from his younger sister, his son Tualla was born, whose descendants are the Ossetians -Tuals.”(4)

It is also noteworthy that the result of Timur’s campaign was a multiple increase in the population of the Alagir Gorge, which even led to the immigration of some Iranians to Dvaletia and the occupation of new territory, while where Timur passed, the country was devastated, settlements were swept away, people were taken prisoner or destroyed, i.e. life stopped. And here, in our case, there is an increase in population and a new living space, moreover, in an area where there was no life before.

Unlike the Georgian chronicles, Arab, Byzantine and other sources call the inhabitants of the Central Caucasus Alans. There are several points of view about their ethnicity. Some researchers connect them with the ancestors of the Ossetians, others with the ancestors of the Balkars and Karachais, and still others with the ancestors of the Ingush.

Agreeing with Ossetian scholars that before the arrival of the Tatar-Mongols, Alans lived in Ossetia, we categorically disagree that the Alans were the ancestors of the Ossetian-Ironians, therefore, under the term Alans-Oats, in our opinion, should be understood as the ancestors of the Ingush and Digorians.

The term “Alans” itself could have a broader meaning and include the ancestors of the Karachais, Balkars, Digors, Ingush and Chechens.

According to the map compiled by S.T. Eremyan based on Armenian sources, the Alanian kingdom at the turn of the XII-XIII centuries. localized in the area from the sources of the river. Kuban in the west to the river. Samur in Dagestan in the east. (5) The conclusion of E. Eichwald, obtained on the basis of an analysis of Byzantine sources, agrees with this: “For other Byzantines, the name Albans completely disappears and only Alans are increasingly called in their place, under which they mainly understand the Caucasian mountain peoples as Chechens, Avars, Kists, in general Lezgins and similar Turkic tribes; now they more often call only Abkhazians and Alans, as inhabitants of the Caucasus, like Procopius, and understand by them the Abkhazians living on the western slopes of it, while all the peoples of the highlands living east of them are understood under the general name Alans, among them are not only Ossetians, as Mr. Klaproth believes, but also Chechens, Ingush, Avars, and in general all the Lezgian-Turkic peoples of the Caucasus, who differ from each other in their language, as well as customs and morals, are also considered.”(6)

A significant part of Alania fell on the territory of Ingushetia and Chechnya, starting from the borders of the kingdom of Serir (Avaria) in the east and to Digoria in the west, including Yoalhote. This is indicated by the message of the Arab author Ibn Ruste (X c.): “Coming out from the left side of the possessions of the king of Serir, you walk for three days through the mountains and meadows and finally come to the king of the Alans. The king of the Alans himself is a Christian, and most of the inhabitants of his kingdom are kafirs and worship idols. Then you walk a ten-day journey through rivers and forests until you reach a fortress called Bab-al-Lan. It is located on the top of the mountain. The wall of this fortification is guarded every day by 1000 of its inhabitants; they are garrisoned day and night.”(7)

Another eastern author, al-Bekri (11th century), wrote: “To the left of the fortress of King Serir there is a road leading the traveler through the mountains and meadows to the countries of the king of the Alans. He is a Christian, and the majority of the inhabitants of his state worship idols.”(8)

From these messages it follows that the capital of Alania was located on the land of the Ingush and, in our opinion, could be located in the valleys of pp. Sunzhi and Terek.

It is also noteworthy that most Alans worship idols. Idol worship is a characteristic feature of the ancient pagan religion of the Ingush.

So, A.N. Genko, referring to Ya. Potocki, wrote: “The Ingush also have small silver idols that do not have a specific shape. They are called chuv (Tsououm) and they are addressed with requests for rain, children and other blessings of the sky.”(9)

Worship of the idol Gushmali existed in flat Ingushetia until the middle of the 19th century.

The “ten-day journey through rivers and forests” described by Ibn-Ruste, in our opinion, is an ancient trade route along the river valley. Sunzha, into which many rivers flow from its southern side, and this area was previously wooded. This route went to modern Karabulak, here it branched into two: one went in a westerly direction through the territory of modern Nazran on Yoalhot, the other - to the village of Srednie Achaluki, from where one road went north through the Achaluk Gorge, the entrance to which was guarded by a fortress near the village. Lower Achaluki (Bab-al-Lan?), the remains of which were preserved until recently on the mountain.

on the right bank of the river. Achaluk, (10) and the other went to Mount Babalo (near the village of Gairbik-Yurt), where there was a guard post, the name of which is similar to Bab-al-Lan. It should be said that the Arabs could call any passage in the land of the Alans Bab-al-Lan, including “ArgIi naar” at Yoalhote, which is located between the peaks of ZagIe-barz and Assokai.

It should be noted that the Alans are multi-tribal. Thus, Ibn-Ruste reports that “the Alans are divided into four tribes. Honor and power belong to the Dakh-sas tribe, and the king of the Alans is called Bagair.”(11)

Multi-tribalism is also a distinctive characteristic feature of the Ingush. This division has survived to this day. Thus, the Ingush were divided into g1alg1ay, daloi, malkhi, akkhii, etc. That is why in historical literature and in various chronicles, in ancient times and in the Middle Ages, the Ingush were reflected under various names, such as: Saki, Khalib, Dzurdzuki, Kendy , Unns, Ovs, Alans, Ases, Gergars, Gels, Gligvas, etc.

Modern Ossetians do not have such a tribal division. The Digors and Tuals are not Iranian tribes, but are the result of the assimilation of local residents - the Digors and Dvals - by the Iranian tribe that settled in the Alagir Gorge, and the Kurtatins and Tagaurs are later settlers from the same Alagir Gorge.

It should be noted that in the area between the Terek and Sunzha rivers, archaeologists have discovered catacomb burial grounds of the 3rd-9th centuries. AD - in the area of modern settlements Brut, Beslan, Zilgi, Vladikavkaz, Angusht, Ali-Yurt, Alkhaste, etc. - the inventory of which is similar in form to each other. So, according to M.P. Abramova, “excavations of several catacombs of the Beslan burial ground” contained “inventory of the same period, in particular, close to the inventory of the under-mound catacombs of the 4th century. near Oktyabrsky (Tarsky) on the Middle Terek."(12)

The connection between the finds in the area of the conventional triangle Brut - Angusht - Alkhan-Kala is of fundamental importance for us, because According to legend, Angusht is one of the oldest places of settlement of the “G1alg1ay” people.(13)

Archaeological data indicate that each new culture that replaced each other, from the Koban to the campaigns of Timur, was generally uniform for the entire territory contained between Yoalkhote and the river. Argun, including the later tower-crypt culture, widespread in the mountains of the Central Caucasus, which may indicate, given the continuity of these cultures, the homogeneity of the ethnic composition of the population of this region.

E.S. Kantemirov and R.G. The Dzattiats note that “cemeteries that even in detail resemble the burial goods of the Tara burial ground have long been known in Chechnya and Ingushetia and also, without any doubt, belong to the Alanian monuments... The fact that monuments similar to the Tara burial ground will be repeatedly discovered in the North Caucasus from the plains to the highlands, there is no doubt, because even medieval authors noted the great overcrowding and density of the Alan population. The Tara burial ground shows that it is ethnically homogeneous and there is no need to connect it with any other ethnic group.”(14)

Folklore data also indicate that the Ingush lived in the Sunzha River valley. Thus, the legend about Beksultan Boraganov, recorded in the 19th century and describing the events of the 15th century, says: “When they reached the Nasyr River, there they met many of their kunaks, i.e. Galgaev. There were dense forests along the banks of the Sunzha and Nazran rivers... Beksultan Borganov liked this place, i.e. Nazranovskoe And he asked the Ingush: “Whose places are these?” The Ingush answered: “This place belongs to us,” and pointed out the border to a distant place.”(15)

The legendary song “Makhkinan” also reminds us of that distant era: “No one remembers when it was... it must have been 300 years ago. Our people at that time, rich, living in the Doksoldzhi valley (lit.: “Big Sunzha.” - B.G.) multiplied quickly to the Achaluk Mountains and would have lived until now, if not for the devil, who was annoyed that people were living freely... "(16)

F.I. Gorepekin emphasizes that “during their long existence, they (the Ingush - B.G.) were known under various names... for example: in, an, biayni, saki, alarods, gels, amazons, etc., and the latter, descended from them and existing now: Galga, Angusht. From their family - Khamkhoy - came up to 25 generations, who gave settlers to Chechnya and the Kumyk plane, forming villages there. Andre or Endery"(17)

So, before the invasion of the Tatar-Mongols, Ingush settlements on the plain occupied almost the entire valley of pp. Terek and Sunzha. Thus, Ingushetia was the most significant territory of Alania in terms of size. Ingush settlements, in addition to the mountains, occupied the plain, before the invasion of the Tatar-Mongols, almost the entire valley of the Terek and Sunzha rivers.

Returning to the ethnonym “Alans”, let us quote from the work of Yu.S. Gagloity “Alans and questions of ethnogenesis of Ossetians”: “In his work “On the history of the movement of Japhetic peoples from south to north” N.Ya. Marr strongly argued that scientists hastened to assign the name of Caucasian Alans to the Ossetians, actually the Irons, and that the Ossetians cannot be identified with the Alans, since “Alan, as it has now turned out, is one of the plural forms of the indigenous Caucasian ethnic term, based on the sounding “al” "or, with the preservation of the spirant - "hal".

(Marr N.Ya. On the history of the movement of Japhetic peoples from the south to the north of the Caucasus. -

News of the Imperial Academy of Sciences. VI series. Ptg. 1916. No. 15, p. 1395.)

These remarks made in passing actually have nothing to do with the actual state of affairs, for both the Iranian character of the term “Alan”, which goes back to the ancient Iranian “Arian”, from where the self-name of the Ossetians Iron, and the absence of this term among the indigenous Caucasian ethnic names , are completely obvious.”(18)

In our opinion, Yu.S. Gagloity is wrong in asserting the absence of the term “Alan” among the indigenous Caucasian peoples. On the contrary, since according to N.Ya. For Marr, this term is derived from Khal (Al), therefore, of all the Caucasian ethnic names, the only one corresponding to it is Ingush - “gIa-l(gIa)”, which was argued in the works of N.D. Kodzoeva.(19)

We believe that the ancient term “Alan” is not related to the ancient Iranian “Ariana”, and therefore the connection between the terms “ir” and “Alan” is untenable.

The term “Alan” (“Halani” of ancient and European authors), which is a common collective name for the ancestors of the Karachais, Balkars, Digors, Ingush and Chechens, could arise from the name of the deity “Khal” (options: Al, GIal, Gal, Gel ). People who worshiped this deity could be called Alans, Khalans, Khalibs, Khalis, Khels, Gels, GIalgIai.

The veneration of the god Gial was most widespread among the Ingush and existed until the end of the 19th century. The pagan temple Gial-Erd was located near the village. Shoan, the top of the mountain on the right bank of the river. Assy is called Gial-Erd-Kort (“Top of Gial-Erd”). The G1almi-khi river flows through the country of “GialgIay”. Chechens in the past also worshiped the god “Gial”.

As for the term “as” (“yas”), it practically denoted the same tribes, i.e. ancestors of the Karachais, Balkars, Digors, Ingush and Chechens, i.e. Alans. Depending on the location of the action, the Asami could be the ancestors of any of the people listed above. But since the territory of the Ingush was more significant, the name “as” most likely meant the Ingush. This probability increases even more if we consider that in the Ingush onomasticon there are names of aces of medieval authors: Kulu, Taus, Uturk, Polad, Khankhi, Borahan, Berd, etc. There are also a number of toponyms: r. Assa, b. Adj (Achaluk), b. Sevenets (Sunzha), Dedyakov and others.

Medieval authors indicate that “the name (Alania) came from the Alan people, who in their language are called as.”(20) The ethnonym “Alan”, therefore, is a collective name, which Arab and other medieval authors used to designate the indigenous inhabitants Central Caucasus. In our opinion, these inhabitants were the ancestors of the Ingush, known under various names. Considering that one of the self-names of the people is “as”, we will show that by ases (jasses from Russian sources) we mean the ancestors of the Ingush.

Firstly, of all the North Caucasian peoples, the only one who calls himself “as” is the once numerous Galgai (Ingush) tribe Asda (Ozda), which after leaving With plains to mountains under the onslaught of the Mongols and Timur, lived in Mountainous Ingushetia and had more than two dozen villages.

There are many facts about the Mongol war in the country of the Ingush. Thus, Rashid ad-Din reports that “The Horde and Baydar moved from the right wing and came to the Ilavut region; Barz came against (them) with an army, but they defeated him” (21)

According to information from an old resident of the village. Angusht Dzhabrail Kakharmovich Iliev, born 1910, mountain west of the village. Angusht is called Ilovge and the area at its foot is called “Bairs viinache” (“The place where Byars was killed”) or “Bairsanche”. According to the stories of old-timers, in particular Chakhkiev Lom-Lyachi, who died in 1934 at the age of more than 100 years, the area adjacent to the village. Angusht was one of the oldest places of residence of the Ingush.(22)

In the word “Ilavut” from the chronicle, the root is “Ilav”, and “-ut” is the usual Mongolian ending, which is often found in Mongolian chronicles (cf. asut, orosut, serkesut, etc.). In the toponym “Ilovge” the root is also “Ilov”, and “-ge-” is the directional toponymic suffix.

Thus, we can conclude that the “Ilavut region” is nothing more than the area adjacent to Mount Ilovga, and “Barz” is the leader of one of the Ingush detachments that fought the Mongols - Bayrs.

Secondly, the Assa River (As-khi or Es-khi - “river As (Es)”) flows through the territory of the Ingush, the name of which contains the element “As (Es)”. Residents of the river valley The Assa could well have been called Aesir.

Thirdly, the left tributary of the river. Sunzhi in the village area. Akhki-Yurt is a river called Esei. where the village of the same name was located.(23)

It should also be noted that in the Ossetian language there are no ethnonyms corresponding to the ethnonyms “Alan” and “Asy” / “Osa” / “Yasy”. Even the word “Ose-tin” is not Ossetian in origin.

List of used literature:

1. Kaloev B. L. Ossetians. M., 1967. p.25

2.Tmenov V.Kh. Several pages from the ethnic history of Ossetians - Problems of ethnography of Ossetians. Ordzhonikidze, 1989. p. 114.

3. Kaloev B.A. Op. op. p.26

5. Eremyan S.T. Atlas for the book “History of the Armenian People”. Yerevan, 1952.

6. Eichwald E. Reise auf dem Caspischen Meere und in den Kaukasus. Berlin, 1838, Band II. S.501. Translation by B. Gazikov.

7. Ibn-Ruste. Book of precious stones. Per. ON THE. Karaulova. — CMOMIK, XXXII, pp. 50-51

8. Kunik A., Rosen V. News of al-Bekri and other authors about Rus' and the Slavs. Part 1, St. Petersburg. 1878, p.64

9.Genko. A.I. From the cultural past of the Ingush. ZKV. T.V. M-L., 1930, P.745

10.Map of the Autonomous Region of Ingushetia. 1928.

11. Ibn-Ruste. Book of precious stones. p.50-51

12.Abramova M.p. Catacomb burial grounds of the 3rd-5th centuries AD. central regions of the North Caucasus. - Alans: history and culture. Vladikavkaz. 1995., p. 73

13. Information from Dzhabrail Kakharmovich Iliev, born in 1910, recorded by the author in April 1997. The audio cassette with the recording is stored in the author’s personal archive.

14. Kantemirov E.S., Dzattiaty R.G. Tara catacomb burial ground VIII - IX centuries. AD Alans: history and culture. Vladikavkaz. 1995. p. 272

16. Newspaper "Caucasus". 1895. No. 98

17. Gorepekin F.I. About the discovery of the existence of writing among the Ingush in ancient times. CFA RAS, f. 800, op.6, d.154, l.11

18. Gagloity Yu.S. Alans and questions of ethnogenesis of Ossetians. Tbilisi. 1966, p.27.

19. Kodzoev N.D. Origin of the ethnonyms “Alan” and “g1alg1a”. — World in the North

The Caucasus through languages, education, culture. (Abstracts of reports of the II International

Congress September 15-20, 1998). Symposium III “Languages of the peoples of the North Caucasus and other regions of the world.” (Part I). Pyatigorsk 1998. p. 4 7-50; His own. Alans. (Brief historical sketch). - M.. 1998. pp. 3-5: His own. Essays on the history of the Ingush people from ancient times to the end of the 19th century. Nazran, 2000. p.80-81

20. Journey to Tana by Messer Joseph Barbaro, Venetian nobleman. -Ossetia through the eyes of Russian and foreign travelers. Ordzhonikidze. 1967. p.23

21. Rashid ad-Din. Collection of chronicles. T. II. M.-.L., I960. p.45.

22. Information from Dzhabrail Kakharmovich Iliev, born in 1910, recorded by the author in April 1997. The audio cassette with the recording is stored in the author’s personal archive.

23.Map of the Caucasus in the 40s. XIX century Map department of the Russian National Library. St. Petersburg

| Digorians | |

| Modern self-name | Digoron, digorænttæ |

|---|---|

| Number and range | |

| Language | Digor dialect of the Ossetian language |

| Religion | Orthodoxy, Islam, traditional beliefs |

| Included in | Ossetians |

| Related peoples | Ironians |

The Digorians make up the bulk of the population of Digoria - the western part of North Ossetia (Digorsky and Irafsky districts of the republic) and the Ossetians living in Kabardino-Balkaria (the villages of Ozrek, Urukh, St. Urukh, etc.). At the beginning of the 19th century, a number of Digor families from the foothill villages of Ket and Didinata moved to the territory of the modern Mozdok region. Here, on the right bank of the Terek, two large settlements of Digorians arose - Chernoyarskoye (Dzæræshte, 1805) and Novo-Ossetinskoye (Musgæu, 1809)

Unlike the rest of Ossetia, which joined the Russian Empire in 1774, Digoria became part of the Russian Empire in 1781.

In the first half of the 19th century, Digorians professed both Islam and Christianity. The Russian government, seeking to separate Christians and Muslims, resettled the Digorians to the plain and in 1852 the Free Christian and Free Mohammedan villages were formed. Mozdok Digorsk residents from the villages of Chernoyarskaya and Novo-Ossetinskaya are also Christians. A considerable number of Muslim Digorians moved to Turkey in the second half of the 19th century, where they settled compactly near the city of Kars (the villages of Sarykamysh and Hamamli)

Nowadays, most of the Digor residents of the Iraf region and those living in Kabardino-Balkaria profess Islam; predominantly Christians live in the Digor region. The influence of Ossetian traditional beliefs is significant both among nominal Muslims and nominal Christians.

Video on the topic

Digor dialect

Writing in the Digor dialect existed (in parallel with writing in the Iron dialect) from the very appearance of Ossetian writing on a Russian graphic basis, that is, from the middle of the 19th century. However, gradually the proportion of writing in Ironian, which formed the basis of the Ossetian literary language, increased, which at times led to an almost complete cessation of the printing of Digor texts.

From the time of the establishment of Soviet power until 1937, Digor was considered a separate language, textbooks and other publications were published. However, in 1937, the Digor alphabet was declared "counter-revolutionary", and the Digor language was again recognized as a dialect of the Ossetian language, and the progressive Digor intelligentsia was subjected to repression.

Culture

- Monument to the poet Blashka Gurdzhibekov in Vladikavkaz and Digor.

- State North Ossetian Digorsky Drama Theater - in Vladikavkaz,

- Drama folk theater of regional significance in the city of Digora,

- Song and dance ensemble "Kaft", Digoræ,

- Statue of Jesus Christ with open arms (similar to the statue in Rio de Janeiro) at the entrance to the city of Digoræ,

- Walk of Fame in Digoræ.

- Park of culture and recreation named after the conductor of the Mariinsky Theater (St. Petersburg) Valery Gergiev in Digor.

- Newspaper "Digori habærttæ" ("News of Digoria", Digori district newspaper)

- Newspaper "Digoræ" (republican newspaper)

- Newspaper "Iraf" (Iraf district newspaper)

- Life of the "Iraf region"

- Magazine "Iræf" (literary magazine of the Writers' Union of North Ossetia-Alania)

- Museum in the village of Zadalesk, Iraf district

- Local Lore Museum of G.A. Tsagolov, Digoræ,

- In the village Dur-Dur, Digorsky district, Museum of the People's Artist of Ossetia M. Tuganov (Branch of the Regional History Museum of North Ossetia-Alania), Vladikavkaz

- In the village of Karman-Sindzikau, Digori district, the work of the People's Artist of Ossetia Soslanbek Edziev is exhibited.

- The monument to Salavat Yulaev, the people's hero of Bashkiria, an associate of E. Pugachev, was erected by Soslanbek Tavasiev.

- A native of Digora, Murat Dzotsoev, was awarded the Order of Glory in 1956 during the Hungarian events.

- In the city of Digor, streets are named after Heroes of the Soviet Union who showed courage and heroism on the battlefields of the Great Patriotic War: Astana Kesaev, Alexander Kibizov, Akhsarbek Abaev, Sergei Bitsaev, Pavel Bilaonov, Alexander Batyshev.

- In Voronezh, a street is named after Lazar Dzotov (“Lieutenant Dzotov Street”)

- In the city of Digora, a street is named after Sergei Chikhaviev, an employee of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, who tragically died in 1994 while on duty.

- In Krasnoyarsk, a secondary school and a street were named after the hero of the civil war, Khadzhumar Getoyev, a native of the village of Surkh-Digora, and a bust was erected.

- Monument to Kermen revolutionaries, heroes of the Civil and Great Patriotic Wars in the city of Digoræ,

- In Vladikavkaz, streets are named after Kermenist revolutionaries: Georgy Tsagolov, Debola Gibizov, Andrey Gostiev, Kolka Kesaev, Danel Togoev

- In the city of Vladikavkaz, a street is named after the Hero of the Soviet Union Astan Nikolaevich Kesaev (captain of the submarine "Malyutka").